This is my homemade methodology to evaluate early-stage startups.

It's a simple but thorough checklist that prospective founders, investors, and employees can go through before committing their time or money to a startup.

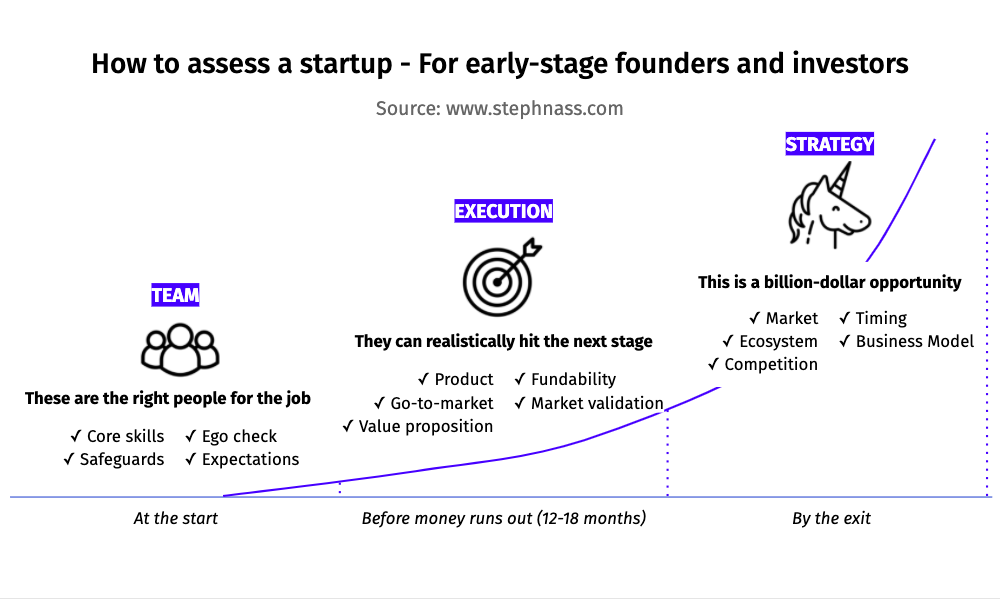

This framework revolves around 3 core questions:

- Team: Are these the right people, both in terms of skills and human fit?

- Execution: Is the next milestone reachable within 12-18 months?

- Strategy: Is this a billion-dollar opportunity?

Before starting, three things. First, this playbook is not about startup valuation. If you are interested in how to value a startup, please take a look here . Second, I've illustrated this playbook with slides from actual pitch decks from Uber, Youtube, Airbnb, etc. You can learn how to build a startup pitch deck by reading this . Critics and suggestions are welcome.

Now, to the good stuff!

Table of Contents

1. Assess the team

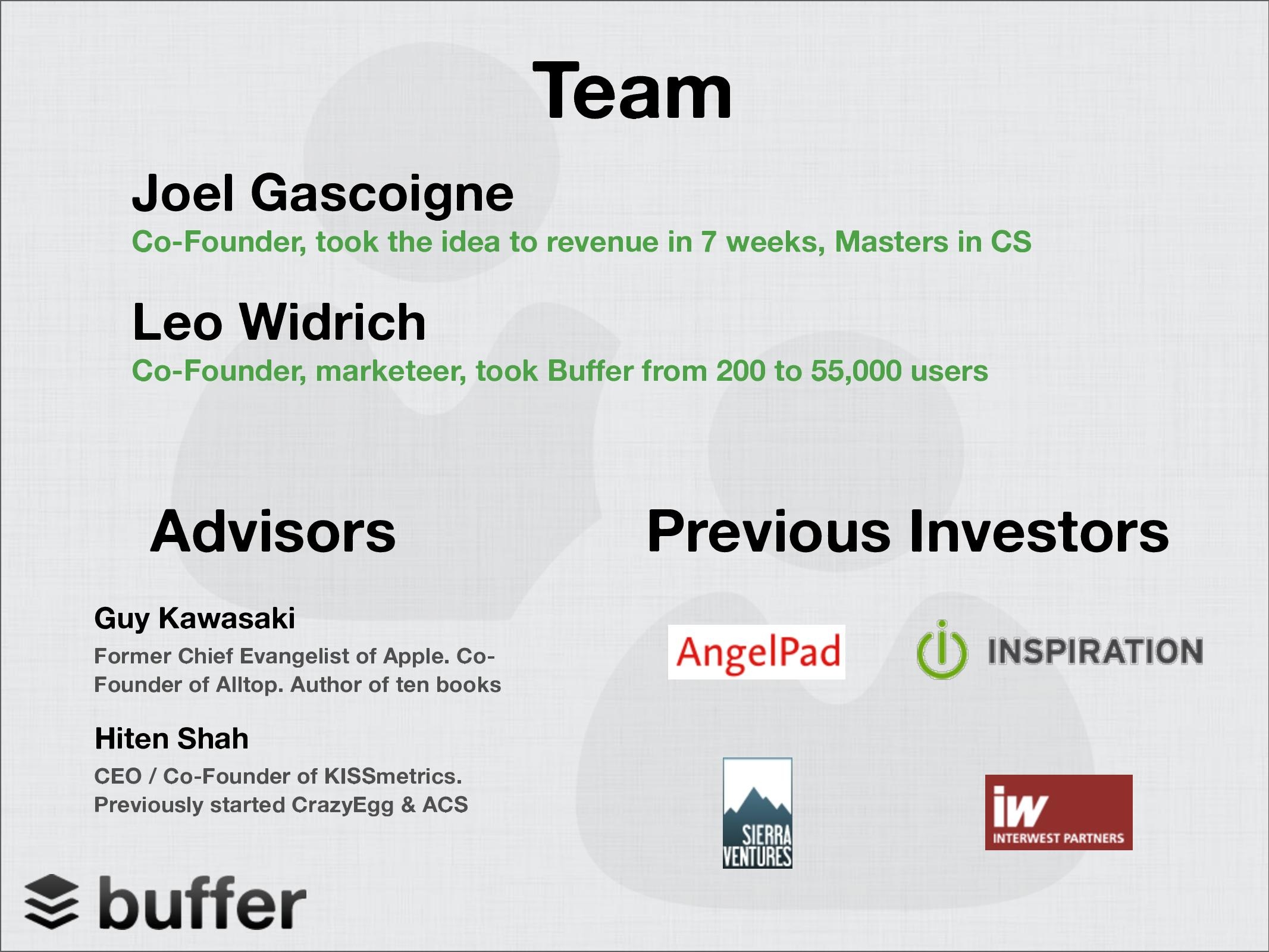

Everybody will tell you — at early-stage, you don't invest in the project, you invest in the people.

The team is most important because it's the only thing that doesn't pivot in a startup. It's the startup that pivots around the team.

1.1 Skills

Does the team cover all the critical skills?

If you build an AI product, you need an AI guy. If you address the Chinese market, you need a Chinese guy. If you develop therapeutics, you need a science guy. Those are the "critical skills". They cannot be outsourced so make sure that the founding team gathers them all. Don't worry about non-critical skills: they can be acquired later through advisors, early employees, consultants, or self-learning.

What is the founders' track record?

Look for signs of excellence in the founder's curriculum – be it professional, academic, or otherwise. Not everybody is a repeat founder with successful exits under their belts, but that shouldn't prevent you from running a thorough background check.

Do the founders bring an unfair advantage with them?

Sometimes, a founder brings an unfair advantage with him:

- A blogger with a massive following in the target market

- A scientist with strategic intellectual property in the field

- A top executive with privileged access to C-level stakeholders

This is natural for teams that have a strong fit with the project and is a great signal overall.

Team slide from Front pitch deck

1.2. Egos

Are there signs of hurt egos?

I don't like the "co-CEO" thing. When I see a co-CEO, I tend to see it as an unresolved ego problem. I may be wrong... This is true to a lesser extent with early-stage COOs when the title is given as a consolation prize to the founder who didn't get to be the CEO.

Is everybody happy with the equity split?

At the end of the day, equity split is a matter of fairness, or more precisely, a matter of perceived fairness. For instance, somebody may think they are entitled to 80% of the company because they brought the idea. They're wrong but there's not much you can do about it – except leaving. Equity calculators like Slicing Pie can help with that. What you don't want is resentment/frustration/ that creeps up over time until potentially bringing the company down.

Is there a significant seniority gap between the founders?

A significant gap in age or experience between founders tends to exacerbate issues. That's what I call the "ex-VP" symptom. I am not saying it cannot work at all, but I would pay attention to that point. Here is one case I have directly witnessed.

An ex-VP at a F100 beverage company partnered with two younger tech guys. On paper, it was a perfect match: he brought industry insights and connections, they brought the tech muscles. They had an ambitious project that made a lot of sense for the industry at the time. They split up five months later, however. According to the two younger guys, (a) the ex-VP was too directive and disregarded their inputs and (b) he was not operational enough - couldn't set up an emailing campaign if his life depended on it - and (c) he felt he was not valued enough for his contributions (while the two tech guys felt the exact opposite).

Team slide from Square pitch deck

1.3 Safeguards

Have the founders worked together before?

Tough times reveal characters. For that reason, it's always better if the founders have known each other and worked together for a significant amount of time e.g. in a previous company. Bonus point if they have done something hard together.

What about a trial period?

Working together for a couple of months before committing is the best way for the founders to "feel" each other if they have never worked together before.

What about the partnership agreement?

A partnership agreement protects the company against future conflicts between founders. It's like a prenup: it states the terms of the divorce before you even get married. That way, the baby is safe even when the parents are breaking apart. A partnership agreement is revised periodically - typically every year - so don't worry about getting it right the first time. Just grab a template online, google the terms and search for common clauses and best practices. The idea is really to have the hard conversations when everybody still has a cool head and can be reasonable. Conversely, having a hard time drafting the agreement is a good hint at future problems in the team. A partnership agreement is a must: no agreement, no partnership.

Team slide from Flowtab pitch deck

1.4 Expectations

Are the founders aligned on the workload?

Don't take it for granted. I've seen too much frustration around that topic. Discuss early and openly about the expected workload, whether weekends are off-limits, etc.

Are the founders aligned on frugality?

You may last a long time passing up on a salary by sleeping on a sofa in your parent's basements. Your co-founder with a wife, 2 kids, and a mortgage may not. Again, communication is key. Sometimes, there will be no solution - and it's better to know early.

Are the founders aligned on company culture?

Sit down with your future co-founder and spend a couple of hours together defining the company culture. It's a fantastic way to reveal personalities and learn about the other. What kind of company do you want to build? What is your management style? What are your core values? At the end of the day, it's a great exercise to assess the founder's personal fit. People who write down the company culture have a better time overcoming hardships.

Are the founders aligned on risks and rewards?

Make sure that each founder understands the risks (high) and the rewards (uncertain). Starting a startup is not a get-rich-quick scheme. If anything, that's the opposite: either get-rich-slow or most likely get-poor-fast.

Team slide from Buffer pitch deck

2. Assess short-term execution

Execution is key.

By short-term execution, I mean the capacity to reach the next milestone that will ensure the company's continuation. In most cases, that would be 18 months and a round of funding.

Think about it. You may have a great vision, a perfect strategy but be in a terrible place to execute. I call it the "consultant syndrome", not to be confused with the "ex-VP syndrome" - although some subjects display quite striking similarities.

Let's review short-term execution.

2.1 Value proposition

Are you trying to solve a problem?

This is the startup sin I've seen the most: starting with a solution then looking for a problem. Don't put the cart before the horses - people pay to solve a problem, not to build your vision of a solution to an unproven problem.

Are you solving one clear problem?

It's a common issue with products like CRMs that can do tons of stuff: the founders never know quite how to market them. Sure, your product can solve a million little problems. But because you can doesn't mean you should. At early-stage, clarity trumps exhaustivity. You need to have a strong angle. So what is a strong angle? It's an angle that speaks to your core target. Which brings us to point #2.

Do you have a clearly defined target?

Yes, that's startup 101, but I still hear outraging answers to that question. Let's make a clear-cut example: say you are a startup that sells an automation software for factories. Your target is not "factories" or "US factories". Your target is "electronics factories located on the US West Coast with 100 to 500 employees that use Oracle Cloud as their ERP." Industry, geography, size, software ecosystem: that's 4 attributes - and we haven't got to the buyer persona yet.

Are you solving a "hair on fire" problem?

You may have heard of the painkiller/vitamin/candy analogy to describe startups. Are you solving a painful, insufferable problem (you're a painkiller) or something a bit less compelling (vitamin, candy)? That's not a qualifying question: Facebook was not a painkiller when it launched, yet it has become the massive success we all know. Regardless, being a painkiller obviously makes going to market easier.

Are you addressing a solvent market?

You may solve a real problem, but if nobody can pay for it, that's probably not a good case for a startup. Maybe start a charity?

Can you quantify the benefit of your solution?

Especially in B2B or deep tech, being able to demonstrate a quantified ROI is a big plus. "We cut compliance costs by 10" is a great way to start a conversation with any bank executive.

Can you articulate use cases for each persona?

I have always been impressed by founders who can clearly articulate their value proposition for each persona and break it down into use cases. To me, that demonstrates a deep understanding of the intersection of their market, target, and solution.

Value proposition slide from Dwolla pitch deck

2.2 Market validation

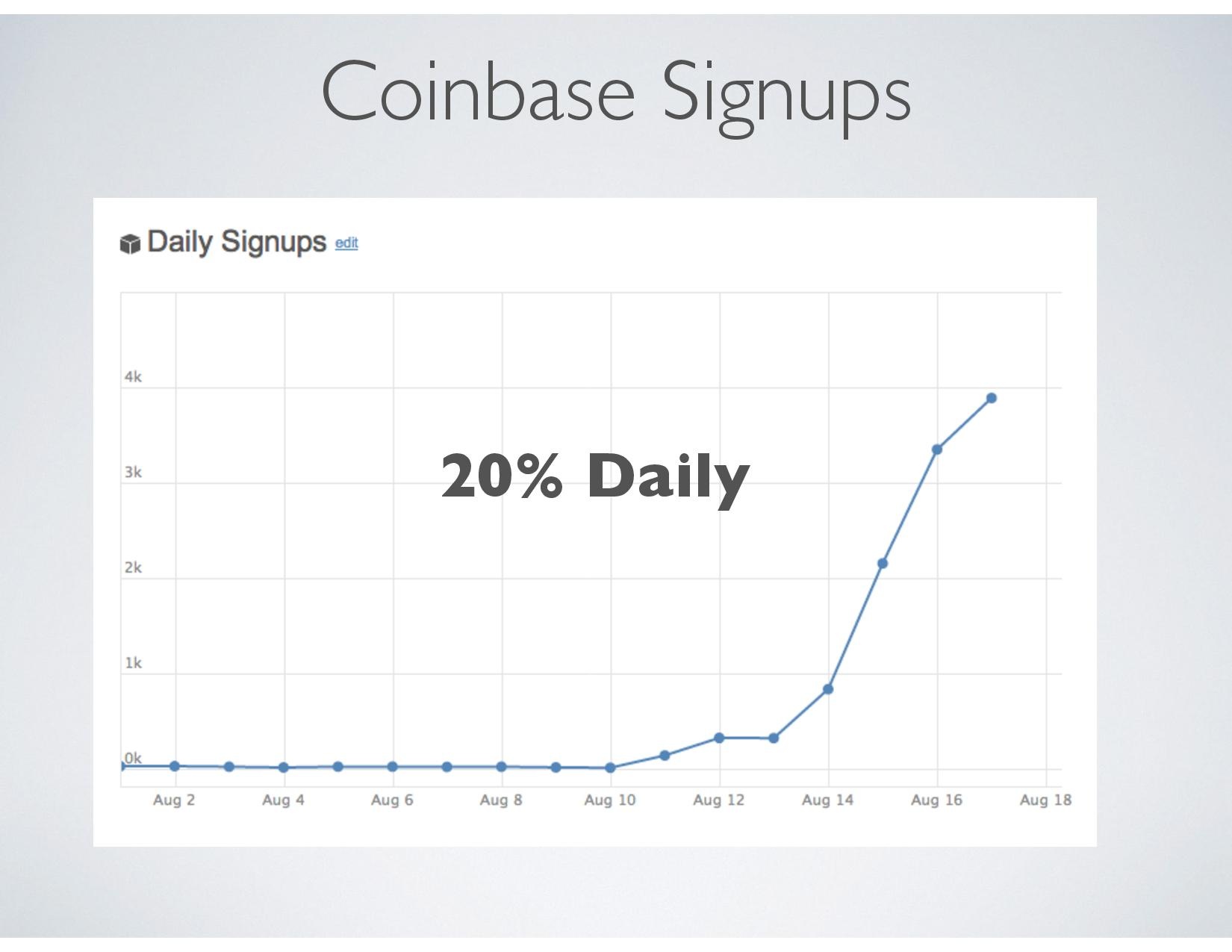

Has the startup reached product-market fit?

A startup that has reached product-market fit (PMF) obviously carries much less execution risk. To learn more about PMF, I suggest reading Brian Balfour's essay on the topic. Typically, PMF indicators for a SaaS startup are retention, acquisition, and intensity of use.

“In my experience, it becomes possible to sustainably grow a product when it reaches around 40% of users who try it that would be “very disappointed” if they could no longer use it.” Sean Ellis

Are there "positive signals" of market validation?

If there is no clear PMF yet, you have to rely on positive signals. Positive signals come in three flavors: clients, investors, and advisors. If the company has any of those, either existing ones or prospective ones, speak with them and make up your own mind. Whenever possible, attend client calls or client meetings: you want to hear it from the horse's mouth.

Market validation slide from Coinbase pitch deck

2.3 Go-to-market

Is there a clearly defined buyer?

Some startups have an obvious buyer. If you're selling fraud detection software for banks, a Linkedin search with the terms "Head of fraud detection" and there is your sales pipeline for the next 12 months. But what if you're selling a Dropbox-like, a Slack-like, or any of those productivity tools? Things become really tricky if you don't have a clearly defined buyer - which brings us back to 2.1: having a clear value proposition.

Is there a clear GTM strategy?

I'll write another post about go-to-market. In the meantime, here are the key elements you should be looking out for:

- A clearly defined geography eg. US West Coast

- A clearly defined segment eg. midmarket

- A clearly defined application eg. your killer feature

- A clearly defined channel eg. see below

Is there a clearly defined channel for customer acquisition?

The channels for customer acquisition are highly dependent on your pricing point. See this classic by C. Janz on the topic. Now, not all go-to-market are equals. If you sell enterprise software, the access to market is notoriously difficult. No wonder it's called "complex sales". In that case, make sure the startup has a way to "hack" its first couple of sales. Maybe one of the founders is a thought leader in the industry. Maybe he can sell to his previous employer. You need to have a silver bullet, because the fight won't be fair and no one will give you a chance.

Is your GTM (eventually) profitable?

At an early stage, you don't really know your CAC or CLV. Nevertheless, you should identify red flags where the GTM profitability will be challenging. A few examples:

- One-time sale models (real estate, car retail) make it hard to recoup your acquisition costs over time

- Small tickets SaaS (eg $10 per month per user) that have no virality and require active sales efforts hardly make a profit

- SaaS models at $10k ACV are considered " dead zones " by some

I am not saying "don't go there". I am saying you should recognize those tricky cases for what they are and have a good answer about how you will crack them. This also relates to the business model (see section 3.4).

Do you have a Sales guy?

Who’s your Sales guy? Who’s gonna pitch your shitty product in front of dozens of prospects until one finds it right? Tech guys most of the time won’t. Consultants won’t. Fighting rejection, writing hundreds of emails, and getting no answers, following every business leads is tough. I mean *really* tough. The most heartbreaking thing I've seen is a great tech team with a weak commercial team.

Go-to-market slide from Airbnb pitch deck

2.4 Fundability

Let's assume bootstrapping is not an option here, and that a seed round is needed.

Is there enough time to raise the upcoming round?

Raising funds takes time. Angels can invest in weeks, but if you're looking at a proper VC round, set aside 6 months from first pitch to money in the bank. Even before that first pitch, some time is needed to prepare the roadshow and brush up the company a bit. So before joining a startup that needs to raise funds, make sure that you and all the co-founders have enough cash to survive for another 6-8 months.

Is there a clear, realistic milestone justifying the upcoming round?

Startups raise funds to reach a specific milestone that will put the company in a favorable position to grow - ideally become self-sufficient, alternatively raise another round. This milestone can be a number of active users (social media), annual recurring revenue (B2B SaaS), a product achievement (deep tech), or even a clinical trial stage (therapeutics). You want that milestone to be clear and consistent with industry practices. You also want this milestone to be reachable within 12 to 18 months, which is the usual time allotted between 2 rounds. For instance, look at the glorious SaaS napkin by C. Janz. Investors expect you to go from 0 to $1M ARR within 18 months and from $1 to $4M ARR 18 months later.

Is the ask realistic?

You don't raise $20M with just a deck of slides. Don't waste your time there.

Do you fit all the other requirements for fundability?

Fundability consists of dozens of data points. Each item in this playbook is a criterion investors look at: team, market, competition, etc. If the startup scores too low on those items, then it's probably not fundable.

Funding slide from Intercom pitch deck

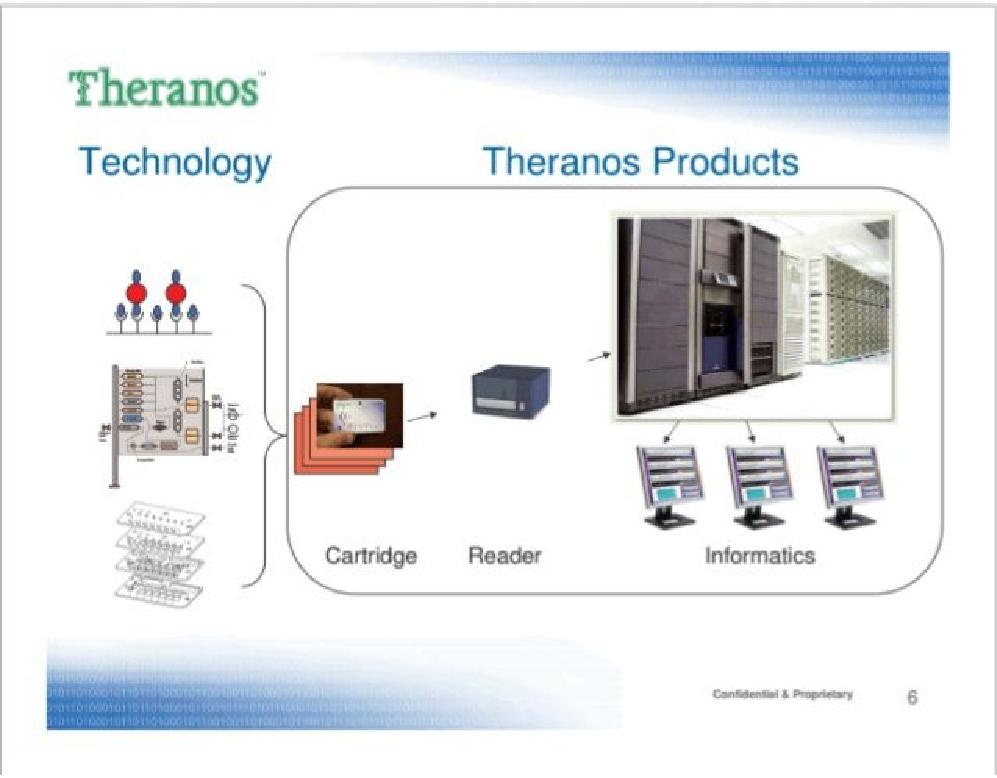

2.5 Product

Is there too little product?

Not having (enough of) a product (yet) is a risk. First, you have nothing to sell, which makes customer validation and fundraising much harder. Second, even if you do raise that seed round, you may end up screwing up your product development and never release any actual product. That's even truer if your co-founders have never shipped anything before.

Is there too much product?

Typical case: the duo of tech founders who burnt through their savings to develop a massive product over 24 months, then look for a CEO to raise $3M - with zero sales. This usually doesn't end well.

How good is the product?

There are two sides to a product. There's the outside, the product that you can see, test, and review. There's the inside, how it works. Good products from the customer perspective can be a sausage factory from the developer perspective. It doesn't matter as long as you are aware of it and plan to rebuild it once scaling becomes an issue.

Product slide from Theranos pitch deck

3. Assess long-term strategy

Now that you have the right team and that you think them capable of delivering in the short-term, let's assess the long-term perspective. Is this really a billion-dollar opportunity?

3.1 Market

Is the market size above $1bn?

By VC standards, the TAM (Total Addressable Market) should be at least $1bn. You can easily find your TAM by googling "CRM market size", "cloud storage market size" or whatever your market is. If your TAM is too small, you'll have a hard time accessing VC money, which deprives you of fuel for growth.

Another story: A good friend of mine is currently building a fantastic SaaS product that solves a real pain point. However, the TAM is well under $100M. He knows he'll have a hard time raising funds with VCs, so his game plan is (a) raising an angel round, and (b) becoming profitable fast. If you ask me, I'd rather join a startup with a great value prop and a tiny TAM than the other way around.

Is the CAGR double-digit?

That's another VC standard: they want to invest in growing markets. Ideally, the startup is entering a market that is about to explode. More realistically, a double-digit CAGR will be just fine. A shrinking market is obviously not a great signal for investors, and should not be for you either.

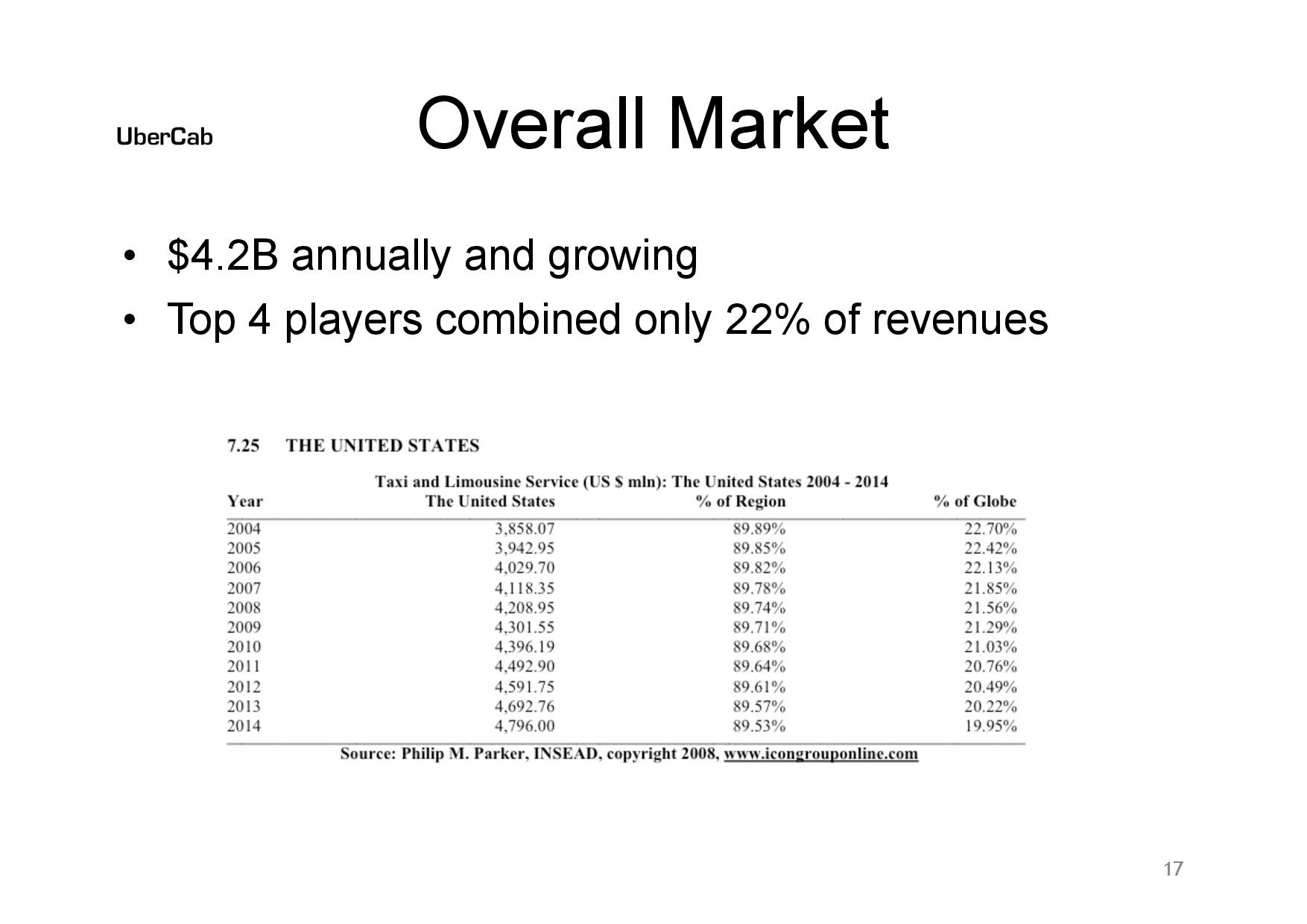

Market slide from Uber pitch deck

3.2 Competition

Is there a competitive advantage/unfair advantage/moat?

Typical competitive advantage factors - branding, quality, customer service, etc. - don't apply to early-stage startups. Instead, identify "operating" competitive advantage i.e. a moat that exists from day 1. That's usually something the founders bring with them: exposure, IP, access to market, etc (cf 1.1).

Is there a clear understanding of the competitive landscape?

At early-stage, competition is rarely the problem. What I find most interesting, though, is discussing the competitive landscape with the founders. Can they clearly explain the positioning of the existing players and they will carve out their niche in that space? Being able to clearly articulate the intersection value proposition, market, product, customer needs, pricing, etc. gives great insights into what's in the founder's minds.

Is there a very direct, well-funded, fast-growing competitor in the same geography?

I said competition doesn't matter, but that's not entirely true. If there is a direct, well-funded, fast-growing competitor in the same geography, you'll have a very hard time getting funded. Few are willing to bet on the challenger.

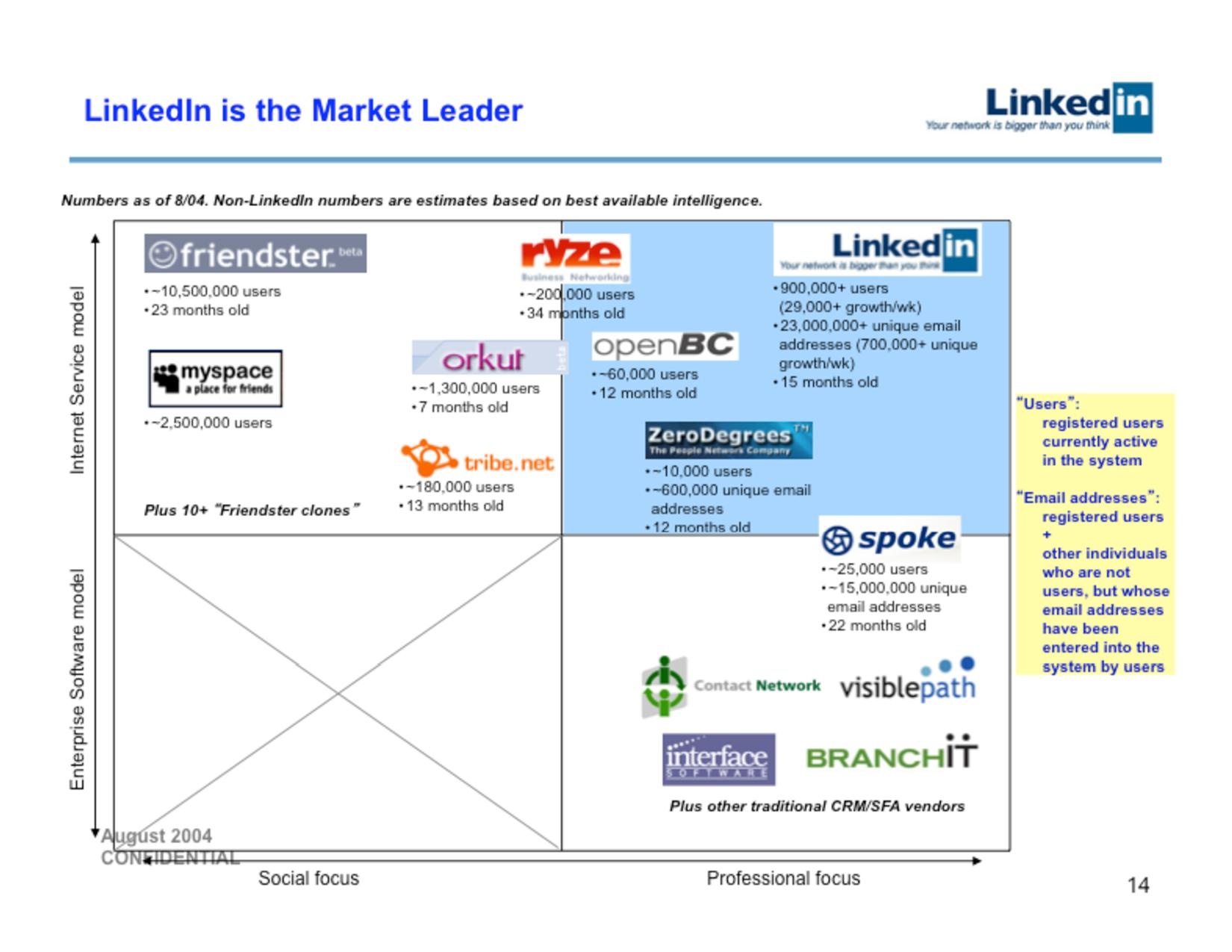

Competition slide from Linkedin pitch deck

3.3 Timing

Is the startup early-to-market or late-to-market?

In theory, being first to market makes sense when you are dealing with network effects (e.g. social platforms) or installed customer bases with high switching costs (eg Nespresso). Being late-to-market makes sense when you are a copycat business (e.g. RocketInternet) or want to let your competitor do the evangelization. But that's all theory. In reality, there's no "right" or "wrong" time to market. There are always examples and counterexamples on both sides. At the end of the day, "time-to-market" is all ex-post reconstruction, so I wouldn't pay too much attention to it.

Is there a good answer to Why now?

"Why now?" is an interesting question to ask. There may be a strong reason why a startup can only happen "now", which also explains why nobody did it before. Here are a few examples:

- Change in regulation eg. GDPR in Europe results in data governance platforms

- Change in technology adoption eg. smartphones with cameras result in Youtube

- Change in society trends eg. veganism results in vegan meal delivery

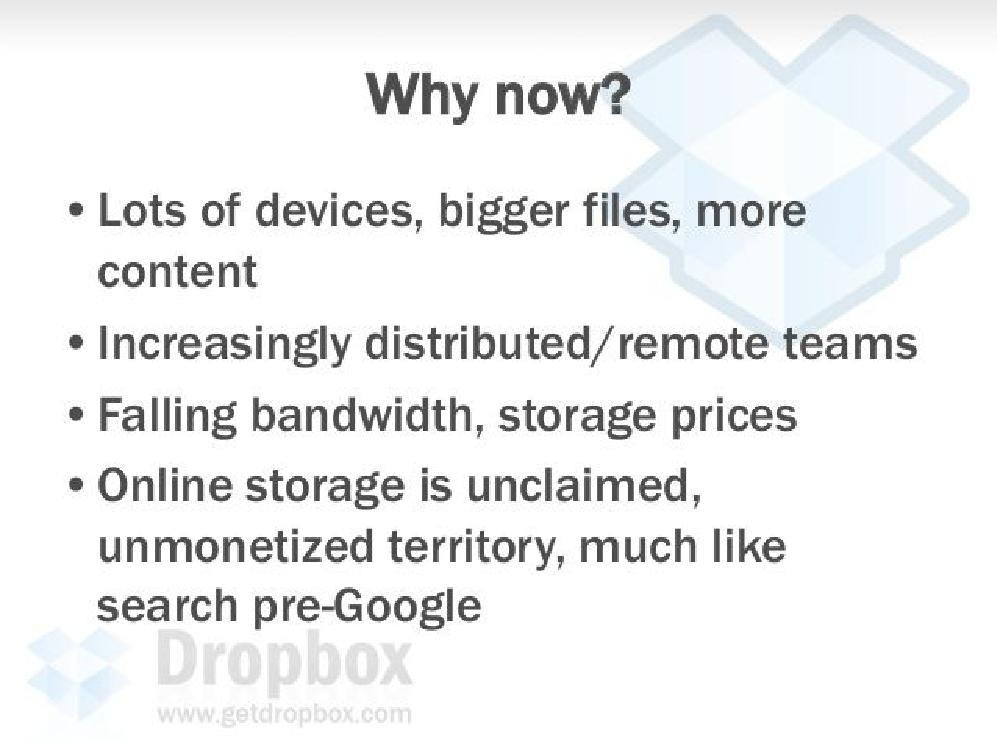

Timing slide from Dropbox pitch deck

3.4 Business model

Is there a clear business model?

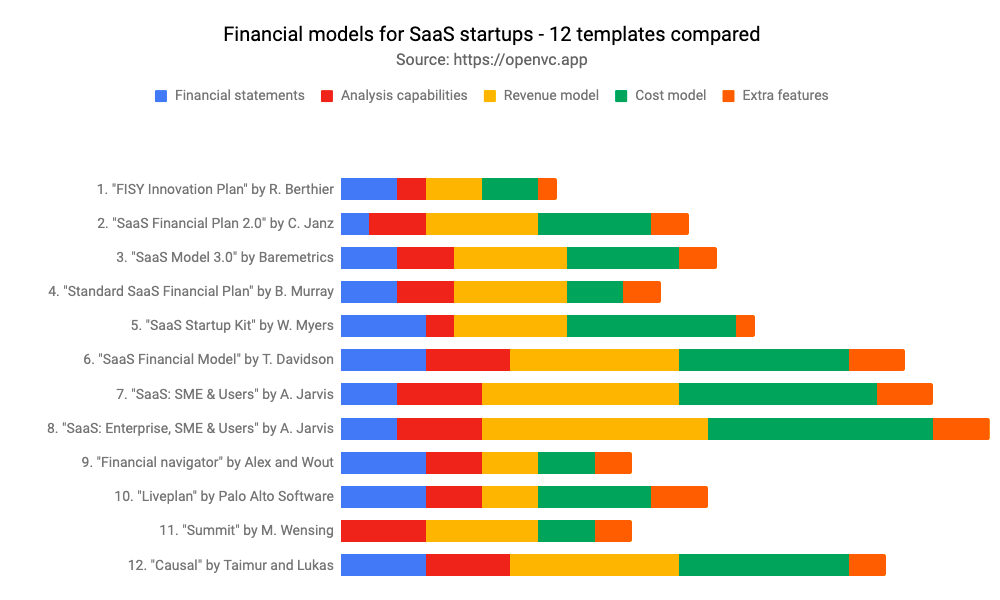

Until recently, it was ok for a startup to slowly figure out monetization and postpone profitability. Famous examples include Facebook, Amazon and Uber. I feel this is less and less true today. Entrepreneurs have become more professionals and investors have become more demanding. Even at the beginning, it's good to have some sense of the key metrics and road to profitability. A financial model can help with that.

Is the business model capital efficient?

The more capital efficient you are, the higher the multiple at the exit. That, and VC are more likely to invest since every dollar they bring generates more value. Capital efficiency may sound abstract when you start, so keep that concept in the back of your mind for now.

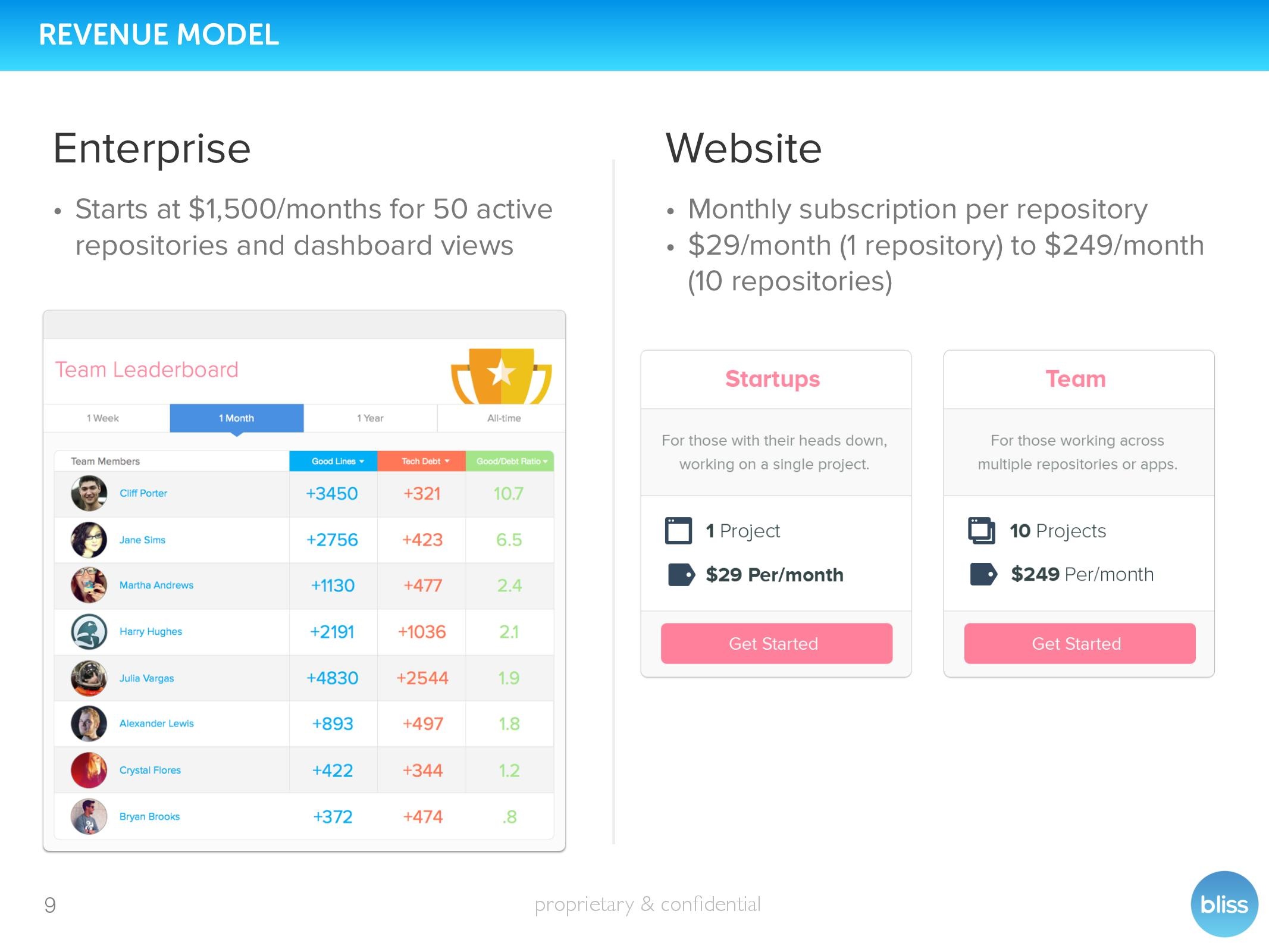

Business model slide from Bliss.ai pitch deck

3.5 Ecosystem

Does the ecosystem provide access to clients?

- If your acquisition is 100% online (eg e-commerce): It doesn't matter much

- If you need to see your clients in person (eg enterprise software): Pick wisely

Does the ecosystem provide sufficient funding?

- USA, China: ample funding at all stages and for all types of projects.

- Small and/or emerging countries: poor funding situation overall

- Middle of the pack (Singapore, France, South Korea, Germany): "Good enough" funding for software startups, still poor for deep tech and other non-vanilla projects.

Does the ecosystem provide access to tech talents?

- For software startups: remote work solves most of the problem o/

- For others: you still need to be near a top ecosystem in your field eg Boston for microfluidics, Shenzhen for hardware, etc.

Does the ecosystem provide access to experienced executives?

If the startup is supposed to scale, you're gonna need an A-team of top execs. People who have taken companies from 1 to 100 more than once, experienced hyper-growth, gone through an IPO once or twice. The Bay Area, New York, London, Boston, Beijing, and Shanghai produce such people. Not so sure about the rest.

Does the ecosystem provide exit opportunities?

It's a circle: no exit, no funding, no startups. What you need is a bunch of large corporations packed together on a narrow strip of land with deep pockets and a strong tendency to M&A. Again, that mostly describes the top five and not much else.

Top 30 ecosystem ranking from Startup Genome

Your startup scored poorly. Now what?

No startup is perfect. Scoring poorly to half a dozen criteria is common when you start. You should address those points nonetheless.

Team problems are the hardest ones to fix. Adding or removing a founder is like open-heart surgery. That's why you better address those points as early as possible.

Execution problems require urgent answers. You need to know ASAP if you can reach the next key milestone before you run out of cash: the infamous cash zero date (CZD).

Strategic problems are not "real" problems. More exactly, they are long-term considerations about how big the startup can get. Scoring poorly on the strategic plan doesn't prevent you from building and selling a great product. This will, however, restrict access to VC funding, since you may not be building a billion-dollar business after all.

There is no miracle recipe for starting a startup.

I like writing formulaic theories, but the truth is, unicorns come in all shapes and forms. Every startup that succeeds is an aberration against all odds so don't let me stop you from starting, The worst that can happen is you will fail - and that's really no big deal.

Now, if this playbook can help your start off strong, that's even better!

Unlock the secrets to startup fundraising 🚀

Use our FREE, expert-backed playbook to define your valuation, build VC connections, and secure capital faster.

Access now