So, you are a founder of a hip new startup that has a high potential for growth, is capable of disrupting the current status quo, and is all the rage across socials?

Awesome! But there are a few minor problems on your path to billions.

You have limited resources, few assets, no bank will return your calls and you haven’t had a rich relative since the Berlin Wall fell.

Enter venture capital.

It is the popular route to go from startup to scaleup for founders across the world. Every founder has a deck in their back pocket and is looking for venture capital funding. But what is venture capital exactly? How does it work? How long does the process take? In this article, we break down venture capital to better prepare founders and aspiring VCs.

Let’s get to it.

Table of Contents

What is Venture Capital?

Venture Capital (VC) is defined as follows:

Capital invested in a project in which there is a substantial element of risk, typically a new or expanding business.

In other words, VC firms are financial institutions that have the capability to gamble their resources on risky endeavors that more traditional firms would pass on.

Why is this the case?

Because startups are inherently risky. According to Explodingtopics.com, 90% of startups fail with first time founders only having a success rate of 18%. Venture capital firms exist to essentially provide funding to these risky enterprises (I.E. your startup).

In simple terms, founders are similar to the intrepid explorers in the age of discovery. They know that untold riches and resources await over the horizon, but need the capital to finance their expedition, hire a crew, and set sail. The patrons who supported them provided the capital in exchange for a cut of the action. In the modern day, VCs play this role.

Let’s say you have taken your startup as far as it could go with the resources you obtained. You have fantastic growth potential, more LOIs than you know what to do with, and a user base that is increasing monthly. However, you need an influx of cash and your network is tapped out. You went to your friends and family, ran a successful Kickstarter campaign, hit your credit card limit, emptied your savings account and are still short of what you need to attain critical mass.

A VC is what you need.

Venture capital is often allotted to small startups with a limited operating history (typically under three years) who have massive growth potential and can continue to expand year after year. Ultimately, the startup offers the VC an opportunity for a high return on their investment.

Popular venture capital firms include Tiger Global Management, Andreessen Horowitz, Sequoia Capital, Kleiner Perkins, 500 Startups, and Lightspeed Venture Partners.

Now that you understand the gist of it, let’s discuss the process.

How To Raise Venture Capital

Founders approach VCs with their deck, business plan, and other documents. This can be as simple as applying to the VC firm directly on their website. Although warm introductions are still the norm and the most effective way to obtain funding, more and more VCs are open to cold outreach. For a complete list of over 4,000 VCs to contact, visit our Openvc.app homepage.

Before a founder contacts a firm, they should conduct their own due diligence on the VC that they are approaching. This is not only a professional move, but an intelligent one. A quick checklist should include:

- Does the startup fit the investment thesis of the venture capital firm? There is no point in reaching out to a firm that specializes in healthcare technology for your space tourism startup.

- Does the startup match the geography of the venture capital firm? Some firms are focused solely on startups in specific regions.

- Is the founding team a match for the VC? Some VCs specifically invest in minority and underrepresented founders.

- Does the startup have anchor capital? Often many VCs won’t lead rounds so finding a firm to be the first check committed is key.

- Does the startup have the required traction? Some VCs only want established startups with traction and specific revenue numbers while others are more open to working with early stage companies. It is essential to know the difference.

- Speaking of stages, it is essential for founders to know which stage of the startup process they are in. A pre-seed startup won’t be a fit for a firm that only invests in a startup that is classified as Series A or above.

So, you checked all of the boxes. You made sure that the deck was clean, the numbers are up to date, and that the advisory board is solid. You reached out and submitted your deck and all relevant material. Now what happens?

Hurry up and wait. VCs receive thousands of pitches. There is nothing more that you can do until you receive that follow up email. More often than not, many founders never receive this email.

But if a startup has potential, the VC will reach out and set up a meeting.

Why?

Because VCs are on the hunt for those high returns that we already mentioned. They are looking for the next investment success story.

You could be that success story.

So you take a meeting with the VC…or two. It isn’t unusual to have multiple meetings with various people in the firm. If there is a real interest, the VC begins the due diligence process. This is investigative research into the startup’s management team, finances, business model, products, intellectual property, and operating history. If the due diligence has negative findings, the VC will pass on the opportunity. However, if everything checks out, the firm will pledge an investment of capital in exchange for equity in the company.

Find your ideal investors now 🚀

Browse 5,000+ investors, share your pitch deck, and manage replies - all for free.

Get Started

What’s Next? Acquisition, IPO, or Failure

But what happens next?

Ideally, the founder uses the funds to grow and scale the business until the next funding round. Ultimately, the goal is for the startup to have a successful exit via an acquisition or an IPO. This process often takes years.

And there isn’t always a happy exit. For every success story of a venture-backed startup that nets billions of dollars for the VC, there are many failures. In fact, the National Venture Capital Association estimates that 25% to 30% of venture-backed businesses fail.

Here are recent examples of venture-backed failures:

- LendUp raised $366 million. Investors included Andreessen Horowitz, Google Ventures, Y Combinator, and PayPal Ventures. They closed shop in 2021 .

- Katerra raised $1.5 billion. Investors included SoftBank, Foxconn, and Khosla Ventures. They went bankrupt in 2021 .

- Quibi raised $1.7 billion. Investors included Goldman Sachs, NBC Universal, JPMorgan Chase. They shut down in 2020 .

Venture capital is indeed a risky business.

The many stages of venture capital

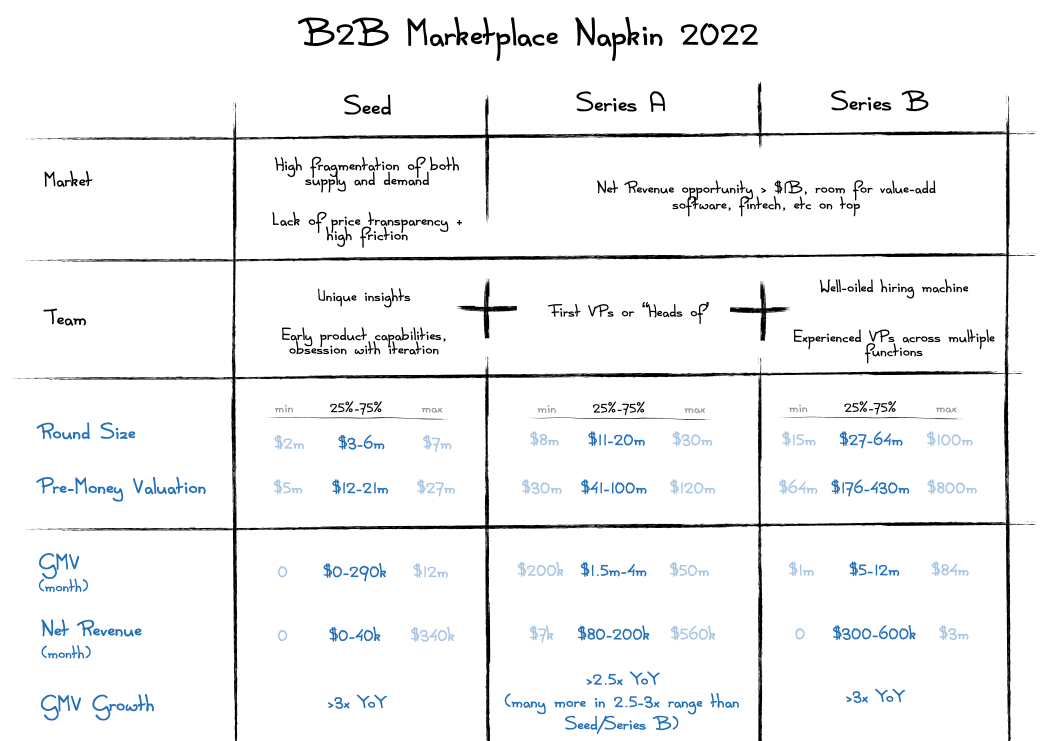

Before reaching out for investment to a VC, it is essential for a founder to know the many stages of venture capital and their associated valuations.

This includes pre-seed (a rarely included stage that is often fulfilled by the founding team and their friends and family), the seed stage, Series A, Series B, and Series C.

See below a fantastic chart done by the good people at Point Nine with a focus on B2B marketplaces.

Additional stages include Series D, E, and F, which are reserved for global companies with valuations in the billions.

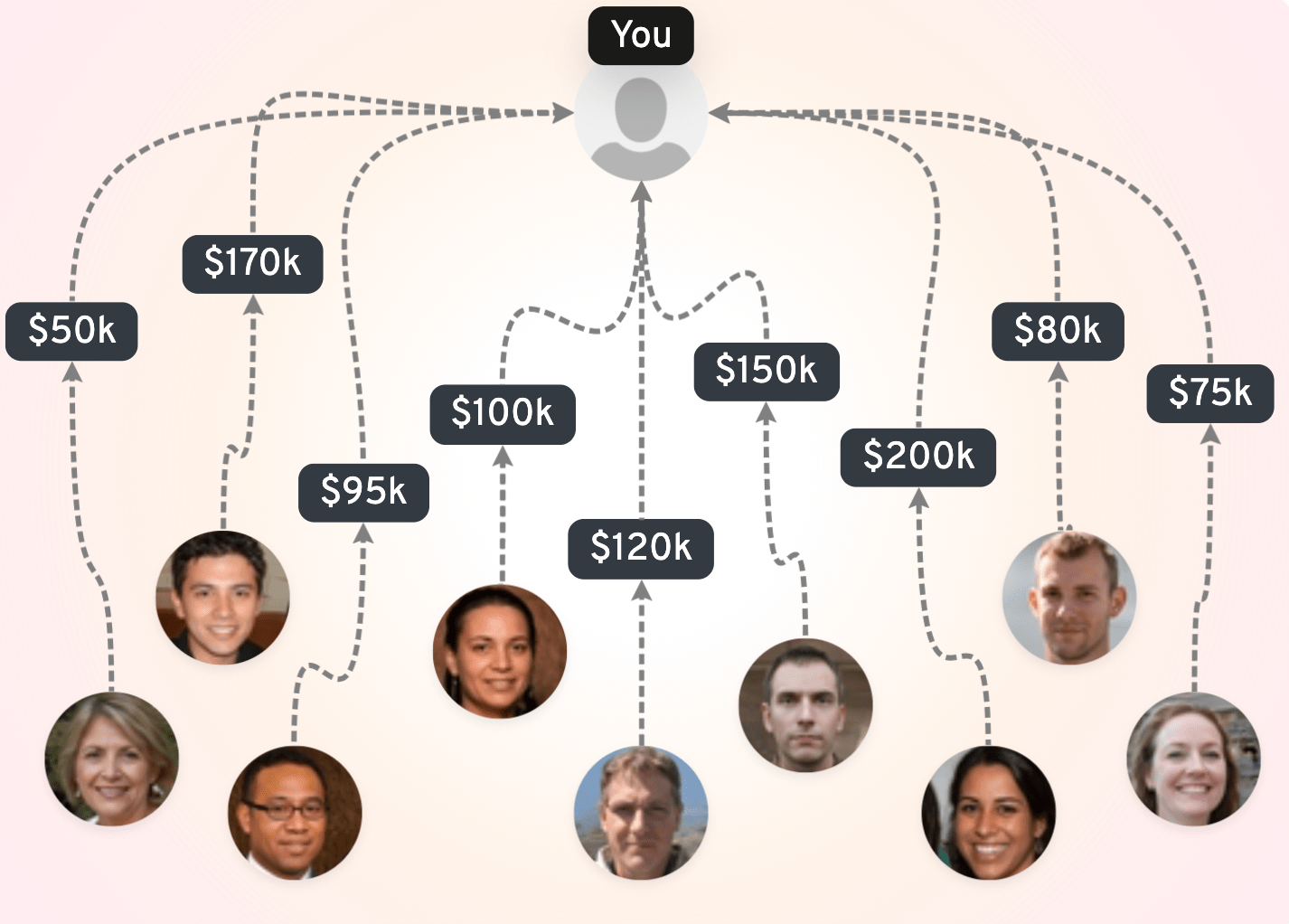

VCs have to make successful investments to return profits to their limited partners (LPs). Seed investments hope for a 100x return while Series A investments desire a return 10x-15x. The later stage investments target 3x-5x.

The graph below by Anna Vital at Adioma.com is now fairly old and the valuation numbers don't apply anymore. However, it remains a great visualization of the funding trajectory from idea to IPO.

From analyst to partner: who does what at a VC firm?

Like most companies, a VC firm is a hierarchy with established roles. This includes general partners, principals, associates, scouts, limited partners, and venture partners.

First and foremost, are the general partners (GPs). They make strategic decisions, guide the investment decisions, develop and guide the fund’s strategy and take board seats in their portfolio companies. They are the leaders of the fund.

Next up are principals. They are the more senior members of a firm who are responsible for sourcing new deals as well as working with founders in the firm’s portfolio. They may get a percentage of the carried interest of the deals they source.

Associates are the employees who conduct due diligence into possible investments for the firm. Their primary role is research and they often bring in deal flow to the firm. Associates have no power to make investment decisions.

At the lowest tier of the fund are the analysts. These are entry-level employees who work with associates on research and due diligence.

But what do all these people do every day? Here is a great breakdown from the Harvard Business Review.

But wait, you have seen people who called themselves scouts? What does that mean? A scout is just what it sounds like. They are people who look for promising new startups and then pass them on to their contacts at the firm. Scouts are not full fledged members of the firm, aren’t paid a salary, and are only compensated on a success basis.

But who funds the firm? That would be the limited partners (LPs) who provide the necessary capital for the firm to make their investments and generate those high returns. As limited partners, they have no sway over the policy of the firm.

What about a venture partner? What do they do?

Venture partners are allies of the fund and serve a supportive role. They are not involved in the firm’s daily activities and are not part of the fund. They provide their own networks and experience and can assist with operations, deal flow, and fundraising. They are paid a commission via carried interest.

A VC may also employ a CFO to manage the standard financial activities of the firm while keeping an eye on the exit for all the companies in their portfolio.

How VC firms make their money - the 2/20 rule

Venture capitalists make money via two methods.

The first is a management fee for managing the firm’s capital (the assets under management). This is 2% of the value of the fund per year. This fee is used to run the general operations of the fund. This includes paying salaries, legal fees, taxes, audits, and other expenses (we have outlined some of the largest firms and their AUM further below in the article).

The second method for VCs to make money is through the carried interest on the fund’s return on investment. This is known as “carry.” Carry is far more profitable to funds than the 2% management fee charged. It is a profit participation fee which the firm sets with the startups in their portfolios. This is usually 20% of the percentage of profits after the fund’s investments are returned to their fund investors. This is known as the 2/20 rule.

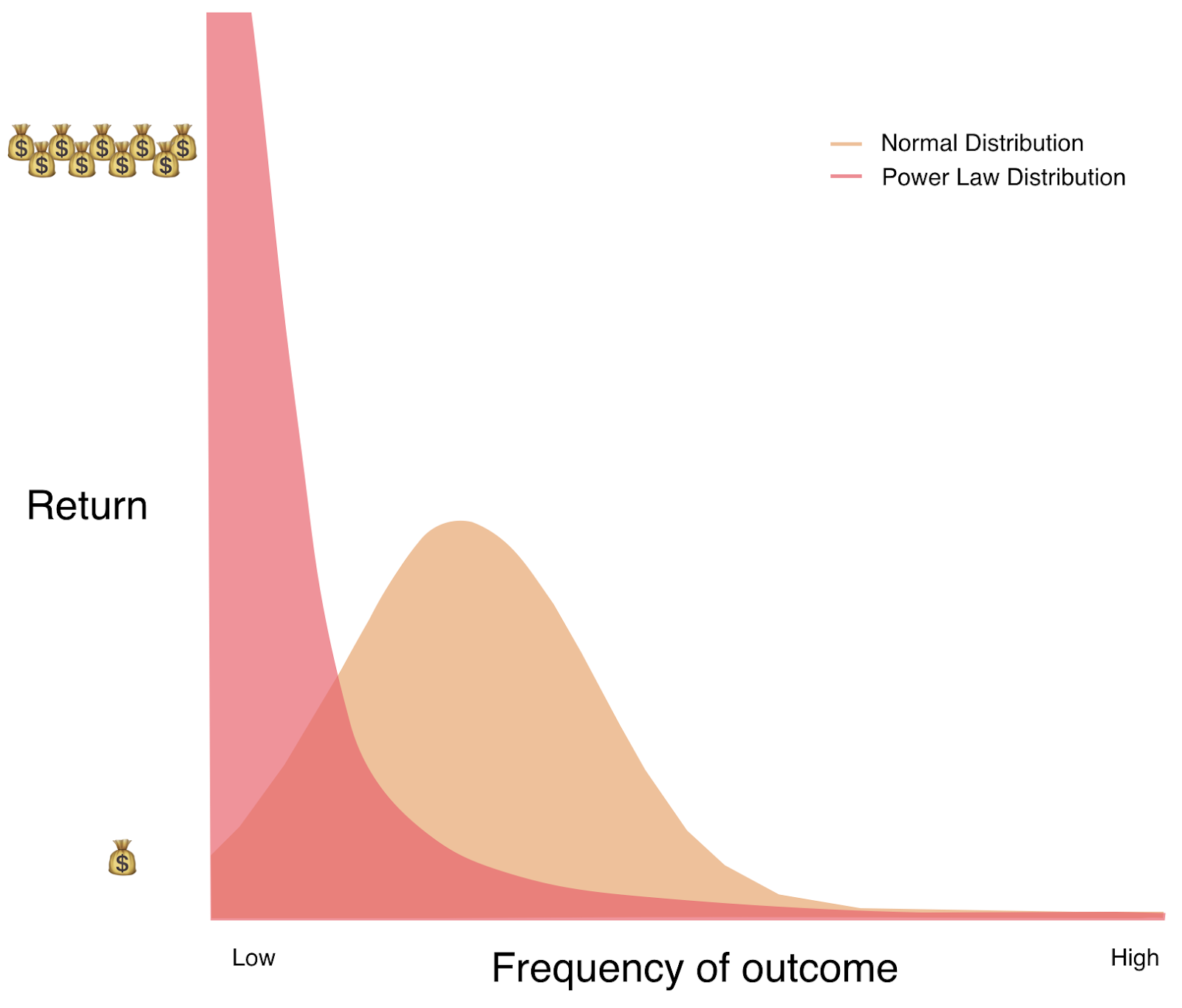

One of the key points for a VC firm to profit via carry is by adhering to the power law. The power law states the fact that venture funds cannot achieve success without at least one bet so extraordinary that its gains return the entire value of the fund to investors.

But how does this work?

Let’s say the VC makes ten investments. All of them have the potential to achieve unicorn status (a startup with a valuation of over $1 billion). Nine of them fail to achieve this status but one investment becomes a unicorn. Then if that one single unicorn investment has a successful exit, the VC will be successful in more ways than one. They will not only have profited for their firm and limited partners, but their success story will attract even more investors. This is the power law in action.

The graph below, courtesy of Hackernoon, is a great illustration of that reality (btw, Hackernoon's guide to understanding investors is great, you should read it!)

Understanding VC portfolio construction and the Power Law

An example of power law is Sequoia's early investment in Apple or Peter Thiel’s early investment in Facebook.

It is all about the return for the VC. The higher return, the better. It is how they make their large profits and solidify their reputation as experts in the space.

Here are a few examples of high returns for VCs, courtesy of CBINSIGHTS :

- WhatsApp was acquired by Facebook for $22 billion, which reaped rewards for the founders and the only venture investor of the company: Sequoia Capital. Their $60 million investment was turned into $3 billion.

- Softbank invested $20 million into Alibaba in exchange for 34% of the company. When Alibaba had their IPO, the Softbank stake was valued at more than $60 billion.

- Keiner Perkins, Sequoia Capital, and Caufield & Byers each invested $12.5 million into Google’s Series B in 1999. In 2005, one year after the Google IPO, each of those investments were worth nearly $4.3 billion.

The adherence to the power law and the desire for high returns has led to a quest for “unicorns.” These are startups whose valuation is $1 billion or more. They are rare, hence the name. Yet if a fund can be the proud investor of a unicorn, they could reap great profits.

Not only that, but because of their model , venture investors NEED unicorns. That's why they won't be interested in just "good" businesses. They want the future Google or Apple, otherwise they cannot cover their losses. It's VC maths, also known as portfolio construction.

(for an in-depth breakdown of portfolio construction, the power law and more, you can read our openvc.app guest post by Rodrigo Ferreira here ).

“We Don't Live In A Normal World; We Live Under A Power Law."- Peter Thiel

How is this all possible?

These high returns are the result of VC ownership in startups. They receive this ownership via an equity stake in the company which is in return for their investment. Additionally, certain VCs will not only provide funding, but expertise in key areas. This includes legal, marketing, and strategic knowledge. And let’s not forget about the relationships! After all, they want a great return on their investment and want to see it be successful.

Now that you understand the gist of it, let’s discuss the process.

What is the market size of Venture Capital?

Just like any industry, VC has a market size, too. And it's big.

Venture Capital is a massive industry. 2021 alone set a new record for VC. Eisner Amper states the following:

“VC investment for all of 2021 ($329.6 billion) not only exceeded the prior record, which was established in 2020 ($166.6 billion), it nearly doubled it. Total 2021 deal count of 17,054 also set a record, far exceeding the prior record of 12,490 deals done in 2019.”

Some of the largest VCs have billions in assets under management (AUM). This includes:

- Andreessen Horowitz (a16z) $54.6 billion in AUM.

- Sequoia Capital with $85.5 billion in AUM.

- Coatue $72.1 billion in AUM.

- Tiger Global $124.7 billion in AUM.

Pitchbook revealed that 2021 in VC saw major exits for VC firms. More than $774 billion in annual exit value was created via venture backed companies that had an IPO or were acquired.

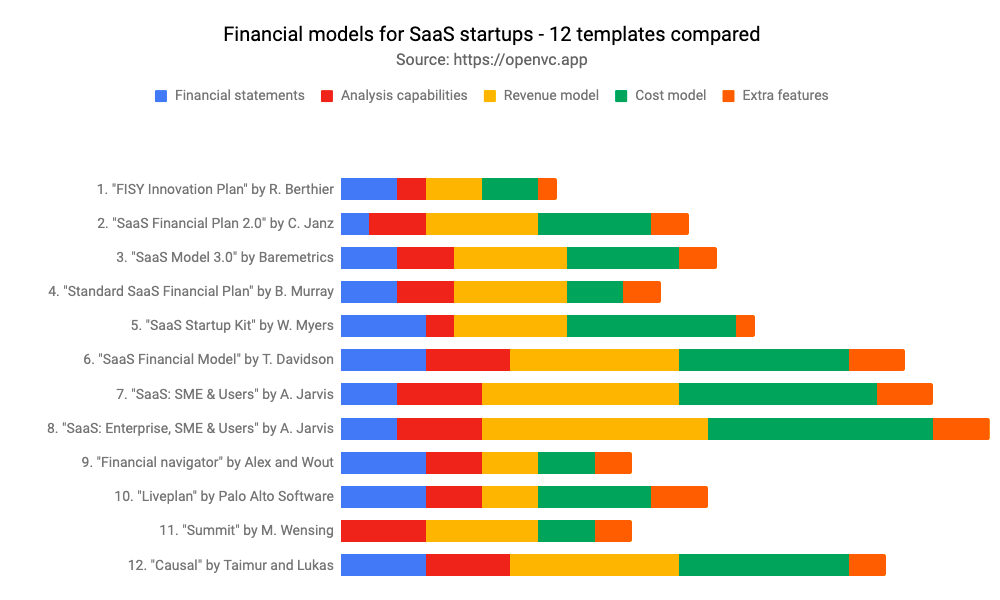

Attached is the chart (courtesy of FactSet ) of the top VC sectors of 2021.

The following is a list of the top VC firms of 2021 (again, courtesy of FactSet )

Although the VC market may be cooling, it is by no means stopping.

Venture Capital vs Private Equity

Venture capital (VC) is similar to private equity (PE) because they both provide working capital to companies with the hope of higher returns. Technically, VC is a form or private equity, but they couldn’t be more different in how they operate and their overall goals. Where VC is the go to for young startups for growth, PE plays a role in more mature companies. These mature companies have a longer operating history and may even be publicly traded entities. Additionally, these companies may be unprofitable. PE firms purchase these companies in an effort to turn them around. The goal for the PE firm is to turn around the failing company and then sell it for a profit.

Whereas VC firms make multiple investments in a variety of companies to mitigate risk and increase the likelihood of success, PE firms purchase 100% of the companies they invest in. This gives them full control of the entity. PE firms possess large amounts of “dry capital” i.e. resources, that allow them to invest vast sums ($100 million or more) in a single company. This grants the PE firm control of the affairs of the company, allowing them to make major changes as well as hire and fire key executives. In simple terms, VCs take a minority stake while PE takes a majority stake.

VC firms take on more risk with their investments, backing risky startups for a higher return if these startups become successful. PE firms face less risk but also a lower return on their investment.

VC firms are limited in how they operate. They only deal in equity deals. PE firms can utilize both cash and debt to achieve their investment objectives.

The length of the investment period wildly differs. VC firms are locked into the startups they invest in for years, knowing that those high returns take time to achieve. PE firms on the other hand seek to quickly capitalize and turn around the companies they invest in.

If you are a fledgling startup, VC is the way to go. If you are the head of a mature company with years of business history, PE is the better option.

A brief history of venture capital

If you were a private company way back in the early 20th century and required capital, you needed access to the few wealthy families that made investments. The Rockefellers and Vanderbilts were primary sources of capital back then. This is a form of venture capital and private equity funding that was not open to the masses. This changed with the formation of the American Research and Development Corporation (ARDC).

As a public company, ARDC raised capital from mutual funds, investment trusts, universities, and insurance companies (bypassing the wealthy families). They made investments into companies that were capitalizing on the technological advancements made during the second world war. ARDC’s biggest success was the result of its investment into DEC (Digital Equipment Company) in 1957. A $70,000 investment in return for a 77% stake was worth $355 million within 14 years. The venture capital industry that we know today was born with ARDC.

By the 1970s, VC was becoming an asset class of its own. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, VCs saw high returns from their investments into companies that are ubiquitous today. You may have even heard of some of them - FedEx, Microsoft, and Apple.

With the rise of personal computing and the mass adoption of the internet, the 1990s were a boom time for VC. Yahoo, Google, Amazon, eBay, Paypal, and more were hitting the market with VC backing. The checks were being cut, the champagne was popping, and the sky was the limit, until the dot-com crash brought the industry back to reality. This didn’t stop venture capital, it only caused it to evolve.

Following the dot-com crash, VCs began an active management style. They not only offered investment, but additional services to the founders in their portfolio.With a focus on software and social media, investment continued to flow. Accelerators and incubators were born, offering early stage companies with high potential access to capital. Micro-VCs launched, allowing for small amounts of capital to be invested in a wide range of companies. What was once a small industry that was geographically centered in New York and California is now a global force. Capitals around the world now have their own VC ecosystems, with new funds launching to capitalize on the opportunities in emerging markets.

Conclusion: Founder - VC Fit?

Founders are obsessed with product market fit but when it comes to obtaining investment for their startup, they need to be aware of the founder VC fit. Not every firm and general partner is a fit for every startup and founder. This is why OpenVC.app is such a great resource for founders looking for their VC fit. Now that you have a better understanding of how venture capital works and how long it takes, you can be better prepared for your startup strategy.

Make sure to do your research on the funds that invest in your sector and industry.

Make sure you understand how the process works.

Make sure you realize that VC investment doesn’t equal success, and that many companies have burned through hundreds of millions of dollars, only to fail.

If you want to play the VC game, do your homework and learn the rules!

Ultimately, make sure that VC is the right move for your startup. You are exchanging your own ownership of your company for investment funding. You may dilute yourself of those high returns that the VCs will celebrate.

Find ideal VCs for your startup today 🚀