In 2020, data collected from 75% of U.S. unicorn companies showed that $4.9 billion of pre-IPO employee stock options went unexercised. This was largely due to the high costs associated with exercising options.

The cost to exercise includes the dollar amount required to purchase them and convert them to common stock, known as the “strike price,” as well as any applicable taxes. The result of excessively high exercise prices is that thousands of employees miss out on the “upside” of successful startup companies, which is typically not recognizable until a company goes public or is acquired.

This is particularly problematic in startups because equity packages often counteract below-market salaries. Employees accept salaries lower than what they could receive in the market with hope that their equity may one day provide a windfall. Unfortunately, many are surprised at the sheer cost when it comes time to exercise.

How is it possible that billions of dollars-worth of stock options are going unexercised? To be clear, this number includes stock options that employees choose not to exercise because they are “underwater.” If the fair market value (FMV) of the shares is below the strike price, there is no reason for the employee to exercise these options.

Still, there are many instances where stock options are not exercised because the financial burden of exercising is too high. While not entirely new, the increasing unaffordability of stock options is highly correlated with a fundamental change in the private markets. Namely, many startups are remaining private much longer in their life cycle, resulting in rising valuations.

Not in the 90s anymore

“Going public” through the IPO process has traditionally been a significant milestone for startups. There are many advantages associated with being a public company, such as access to the public markets, a larger investment base, and the prestige and notoriety that accompanies being a public company.

Public companies also have increased access to banks, and greater access to the debt asset class as a result. Another motivating factor is the opportunity for investors and insiders to finally realize the gains that, up until this point, have only been on paper. Investors and insiders alike eagerly anticipate their nearly instantaneous liquidity that comes from going public.

However, there are also many drawbacks to being a public company. The annual and quarterly disclosure requirements put a large burden on companies, both in costs and time. It is also expensive to go through the IPO process in the first place. Running a public company can invite significant scrutiny into the day-to-day management of the company.

This can stifle teams that are used to “moving fast and breaking things” as private companies. In a public company, you also lose some degree of management control. Minority shareholders have a larger say in the operations of the business and the composition of the board of directors is no longer within the control of the founders.

The rise of the secondary market

Over the last two decades, the private equity secondary market has evolved from a niche asset class to a legitimate option for liquidity in later-stage private companies. This market, allowing the purchase and sale of existing securities in private companies, has ballooned to almost $90 billion in 2021– an increase by a factor of six over the last decade.

This trend has been partially spurred by venture capitalists who invest with eyes on the horizon. Traditionally, investors have expected a return on their investment within five to nine years of writing a check. As companies stay private longer, investors have had to wait longer for distributions, which can strain the VC business model.

Thus, venture capitalists are likely to take advantage of liquidation opportunities created by the secondary market, further increasing its demand and popularity. As this asset class continues to grow, investors and founders will have more opportunities to experience liquidity beyond acquisition and the IPO process.

Find your ideal investors now 🚀

Browse 5,000+ investors, share your pitch deck, and manage replies - all for free.

Get Started

Unicorn factory

The combination of onerous requirements for publicly traded companies and more opportunities to achieve liquidity as a private company has led many companies to remain private longer. Startups who delay, or forgo altogether, the process of going public can capitalize on the cost savings and creative control that accompany being a private company. Generally, successful startups increase in value over time. Thus, the trend of companies remaining private later in their life cycle has led to a sharp uptick in the valuations of still-private companies.

Over the last decade, the upper valuation of private companies has exploded. The number of companies who have achieved “unicorn status,” those that reach a market valuation of $1 billion prior to an IPO, has risen dramatically. In 2021, investors deployed capital into 340 private companies with valuations exceeding $1 billion dollars. In fact, more unicorns were minted in 2021 than in the past five years combined. According to Crunchbase Insights, there were a total of 1,211 unicorn companies in the world as of September, 2022.

A crisis of unaffordability

These increasingly high valuations have very real consequences for the employees who own stock options in the company. You would think that higher valuations would equal more money in the employee’s pockets, and this is directionally true. However, as the valuation of these companies rise, the costs associated with exercising stock options rise as well.

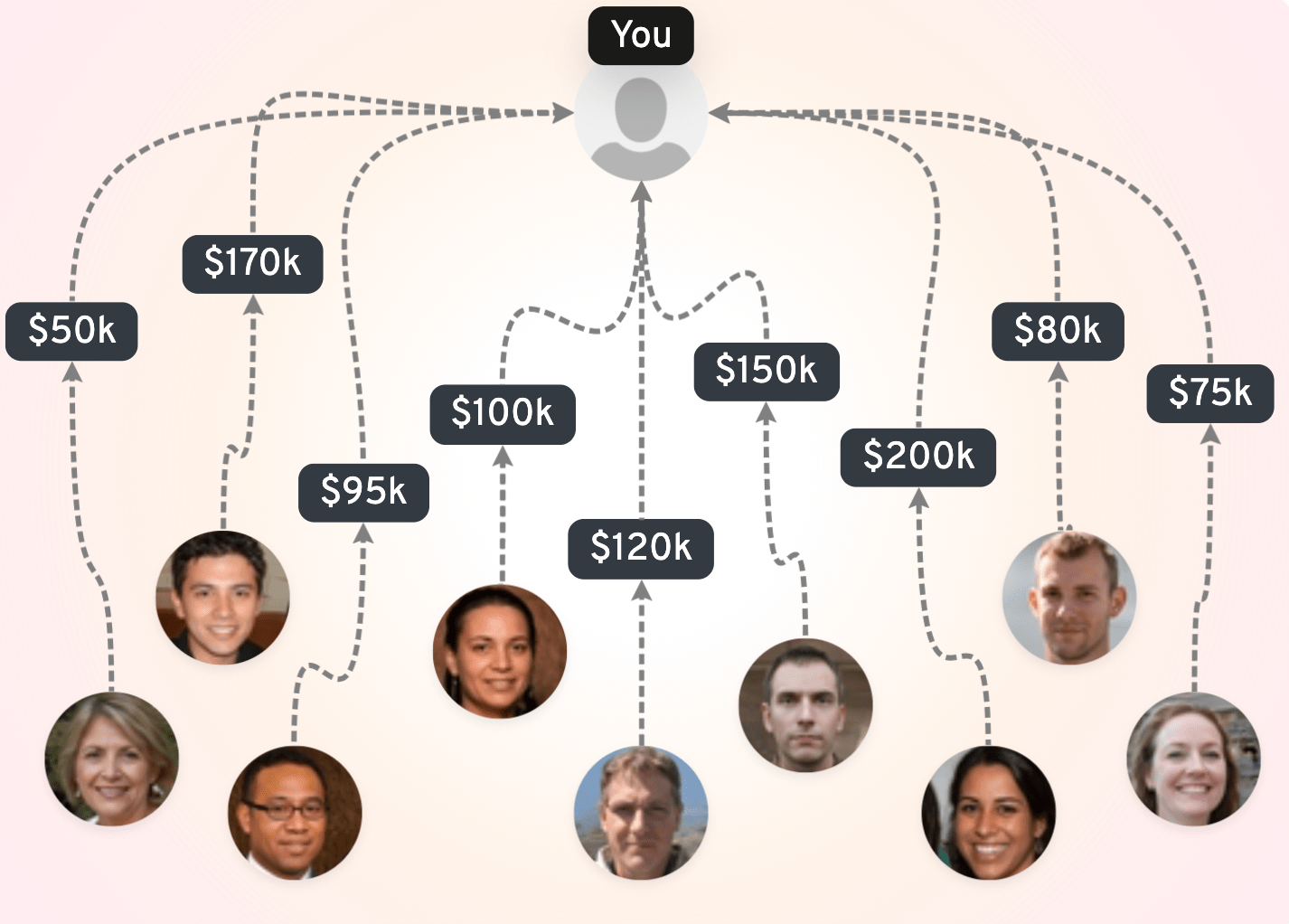

Secfi, an equity planning tool provider, collected data from 75% of all U.S. unicorn companies and found that $4.9 billion worth of stock options expired without being exercised in 2020. On average, the total cost to exercise employee stock options packages was $500,000, nearly double the annual household income of those same employees.

This factor was even more pronounced for “decacorns,” those companies that reach a $10 billion valuation prior to IPO. For these ultra-valuable companies, the average cost to exercise options was nearly 550% of the annual household income of the employees.

The culprit: Alternative Minimum Tax

One might assume that employees would expect these costs and come up with a strategy to avoid them. They are aware of their strike price at issuance after all. However, expensive strike prices are only part of the issue. In fact, the data collected by Secfi showed that 85% of the total cost to exercise was tax.

But wait, incentive stock options aren’t taxed when exercised! Unfortunately, this is somewhat of a misnomer. While it is true that ISOs are not taxed when they are exercised, the employees may be subject to the alternative minimum tax (AMT) during the years in which they exercise their options, particularly if the FMV is high. The AMT can come as a big surprise to employees, because it is not easily understood.

The AMT is a tax system that runs parallel to the ordinary income tax system we are familiar with. It was put in place to correct a perceived “loophole” in the tax system, by which high earners were taking advantage of various tax deductions, lowering their tax burdens considerably. This tax establishes a minimum percentage of income a filer must pay, regardless of the deductions or credits the filer may claim.

The AMT is not frequently discussed, partially because it doesn’t “kick in” until a filer’s income is relatively high. For instance, the AMT only becomes relevant when a couple filing jointly reaches an annual income of $118,100. This is significantly higher than the median U.S. household income of $61,937.

However, this is a threshold that many employees at high-growth startups will easily achieve. Additionally, AMT is not automatically withheld by the employer, which may lead to more employee confusion.

The Alternative Minimum Tax handles stock options differently than the primary tax code does. Even though the employee is not making any tangible money when they exercise, they will have a large “on paper” gain representing the spread between the strike price and the FMV of the shares.

This is considered a “phantom” gain in the eyes of the IRS, and will be factored into the employee’s taxable income for purposes of the AMT. It is important to note that this does not supersede the tax advantages of ISOs . Employees who satisfy the conditions for ISO treatments will still only be responsible for capital gains when they sell their stock options. The AMT can be thought of as “pre-paying” these taxes, and the amount paid will ultimately be deducted from the final tax burden at sale. Still, this can be onerous at exercise when the shares are still illiquid.

AMT rates vary depending on where an employee lives and how much they make. Secfi noted that for their California clients, the rate ranged from 30-38%. Since California tends to be on the high end of the tax spectrum. We will use 30% for the purpose of an example.

Each filer will also have a threshold amount of taxes up until which the AMT will not kick in. This will vary by each employee’s tax situation each year. For purposes of this example, we will assume a threshold of $6,000. Let’s assume that an employee receives 10,000 ISOs with a strike price of $3.00. When she exercises her shares, the FMV has risen to $30/share.

This employee will pay $30,000 ($3.00 x 10,000 shares) out of pocket to cover the strike price. She will also have AMT tax liability of $79,200 ($270,000 – $6,000 AMT threshold x 30%) for a total exercise cost of $109,200. This number is on the low end of what Secfi observed among unicorn employees, and is still well out of reach for most people. This is especially true when there is no guarantee that the options will ever be liquid or will be worth more than the strike price when they are able to be sold.

Out of options for your options?

This brings us back to the dilemma discussed above regarding deciding when to exercise. If you exercise early, you can keep your “phantom gains” low and lock-in the favorable treatment of ISOs. But, exercising early is risky because of the volatility of startups. It can be hard to stomach paying the exercise costs when the ultimate value is so uncertain.

On the other end of the spectrum, some employees may want to wait to exercise until they are more certain what the outcome of the startup will be. However, waiting too long can lead to a massive cost of exercising due to the AMT. Employees may want to avoid this issue altogether and exercise and sell their options in one single transaction. This avoids having to pay the exercise costs for illiquid stock, but the employee will miss out on the favorable tax treatment of ISOs.

Whatever the employee decides, it is no surprise we are seeing such high levels of stock options expiring without being exercised. Higher valuations result in more pronounced phantom gains. Many employees are caught off guard by the sheer unaffordability of their options, and sadly miss out on the upside of successful startups.

Is it time to rethink startup equity?

There are a few strategies used by companies to combat these high exercise prices. Some companies are beginning to allow their employees to “net exercise” their options. In this scenario, the company withholds the amount of shares required to cover the costs of exercising. The employee will end up with fewer shares, but they also won’t have any direct out-of-pocket costs. However, net exercising only contemplates taxes ordinarily withheld by the employer, so this strategy doesn’t help alleviate the AMT burden.

As the secondary market for private company securities becomes more robust, there will likely be more opportunities for companies to achieve liquidity prior to IPO or acquisition. Allowing employees to participate in the secondary market reduces some of the risks associated with exercising early. It is less risky to exercise your options earlier when there are opportunities to achieve liquidity other than waiting for an exit.

Many companies are also extending (or eliminating) the post-termination exercise window. Providing the employee with more time to decide whether or not to exercise their options can help them better evaluate the future of the company and set aside the money necessary to exercise. On the other hand, the longer the employee waits to exercise, the larger the phantom gain will be in most circumstances.

It may be time to move away from stock options altogether. Stock options were invented in a market that no longer exists. Many companies transition to RSUs later in their life cycle, due to high strike prices. But, the AMT acts independently of strike prices: Even if an employee’s strike price is low, waiting too long to exercise can lead to an insurmountable tax bill.

I believe we will see RSUs become the dominant equity over the next decade. Sure, they lack the tax incentives of ISOs, but they also avoid the growing unaffordability issue of stock options. I, for one, would much rather have less tax-efficient equity than stock options that I can’t afford to exercise.

About the author

Luke Versweyveld is a lawyer at Cuvée Counsel, providing startup law on a startup budget. When he's not lawyering, he's building StartupStage - a platform to showcase your startup and compete for free marketing.

This article is intended for educational purposes only, and should not be interpreted as offering legal or financial advice.

Find your ideal investors now 🚀

Browse 5,000+ investors, share your pitch deck, and manage replies - all for free.

Get Started