This post is part of a series on structuring the team and legal infrastructure of a new VC fund. Next post coming out in a week!

In this article, we will provide guidance on how to approach the legal issues related to starting a new VC fund, based on our collective experience as a fund formation lawyer and an investor in emerging fund managers. Coolwater Capital, the “Y Combinator for VC funds,” assesses these documents when underwriting an investment. And at Orrick , we assist fund sponsors with preparing these documents.

We are deliberately omitting from this article certain issues which you should absolutely discuss with your co-founders, but which are not normally contained in your legal documents. These include such issues as: individual partner’s areas of control, budget, T&E policies, explicit strategic focus, decision-making process, etc. These topics are covered in a separate article, Writing the Constitution of your New VC Fund. Finally, employment agreements with partners are a separate topic, which will be covered in a post coming next week.

Brian Cohen, Chairman at Six Point Ventures, said, “Remember that the attorney you hire works for the company and not you. Each partner should have their own representation.”

Table of Contents

1. Economic Issues

The economic issues relate to how the profits and costs of the fund are allocated among the co-partners of the GP Entity and the ManCo Entity.

These include but are not limited to the following items.

1.1 Carried Interest

This is the share of the profits that the GP Entity receives after the investors (limited partners) get their investment proceeds back (and, depending on the fund, a per annum preferred return).

Typically, the GP Entity gets 20% or more of the profits as carried interest, but this percentage can vary depending on the fund size, strategy, and market conditions. The co-partners of the GP Entity need to agree on how to split the carried interest among themselves, and how it should vest it over time, and who is responsible for covering the “GP clawback.” For first-time fund sponsors, an equal split may be appropriate, but for more mature teams, the split may reflect the seniority, contribution, and role of each co-partner.

For example, a typical allocation (assuming no “carry pool”) might be the managing GP/CEO getting 45%, the senior partner getting 30%, two mid-level partners getting 10%, and the junior partner getting 5%.

Additionally, some funds may allocate a portion of the carried interest to strategic advisors/scouts on a deal-by-deal basis. (See How to Find a Job as a VC Scout).

The vesting of carried interest may depend on the investment period of the fund, with variations for more mature fund sponsors. For example, the vesting of carried interest might occur over a five-year period (to coincide with the Fund’s “investment period”) or longer if the “harvest period” is deemed by the co-partners to be critical to a particular fund’s success.

The allocation and vesting of carried interest should also take into account the expectations and interests of the investors, who may want to see alignment of incentives and retention of key persons.

In situations where there is a concern that one or more partners may not be completely committed to the enterprise, “cliff-vesting” or “back-end loaded vesting” structures may be recommended. A “cliff-vesting” structure is one where the entire portion of the carried interest pool (or a significant percentage) becomes fully vested at a specified time rather than becoming partially vested in equal amounts over a period of time. “Back-end loaded vesting” is one where a smaller percentage vests in the early years and the vesting percentage increases over time (e.g., 10 percent vesting the first four years and 20 percent vesting the next three years). Sometimes, the concept of accelerated vesting is built in (for example, upon the death or disability of one of the team members), but often the partners leave issues like this to be decided when any such circumstance arises.

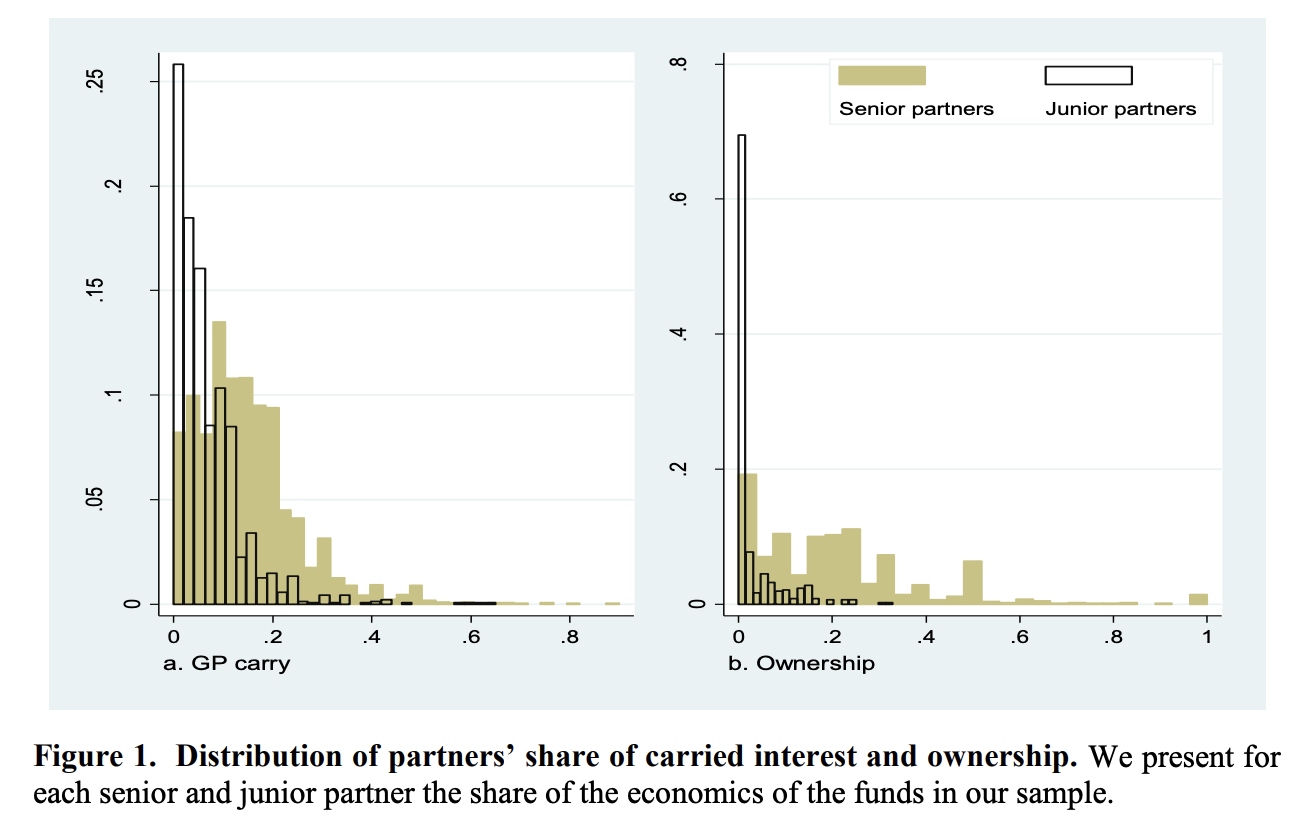

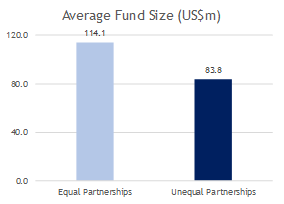

A Harvard Business School study of 717 private equity partnerships by Josh Lerner and Victoria Ivashina examined how “inequality” in the allocation of fund economics between founders and their partners negatively impacted their limited partners:

“We examine 717 private equity partnerships and show that (a) the allocation of fund economics to individual partners is divorced from past success as an investor, being instead critically driven by status as a founder; (b) that the underprovision of carried interest and ownership — and inequality in fund economics more generally — leads to the departures of senior partners; and (c) the departures of senior partners have negative effects on the ability of funds to raise additional capital.”

Blue Future Partners, a VC fund of funds, recommends equal carry among partners. (See “How to Split the Economics”).

Among the VCs who publicly share that they have an equal-carry model are Aleph Partners, Atlas Venture, Benchmark, Charles River Ventures, Eniac, Foundry Group, IA Ventures, Kepha Partners, Madrona Venture Group (in Dan Primack’s Term Sheet, June 6, 2012); and NextView Ventures.

Fred Wilson of Union Square Ventures writes, “once a partner has worked one fund with us together, we are equal partners and share in the profits equally.”

Additional resources:

1.2 GP Capital Commitment

This is the amount of money that the co-partners of the GP Entity contribute to the fund as investors.

Typically, the GP Entity commits 1-5% of the total fund size.

The co-partners of the GP Entity need to agree on how to split up the capital commitment among themselves, and how to fund it. Since each co-partner will likely have differing amounts of capital available to fund the GP’s capital commitment (particularly with respect to first-time funds), the amount each co-partner funds can vary greatly. Nevertheless, the capital commitment should reflect the ability and willingness of the co-partners to invest in the fund ( “skin in the game”), and the credibility and confidence that they convey to the investors.

To quote one prominent NYC CEO, “If someone hasn’t made a lot of money for themselves, why should I believe they’ll make a lot of money for me?” This amounts to a hurdle for people who come from less financially advantaged backgrounds, but we acknowledge that many LPs share this bias.

1.3 Management Fee Income

This is the fee that the ManCo Entity receives indirectly from the fund for providing management services for the primary purpose of paying salaries to employees of the ManCo Entity and to “keep the lights on.” Typically, the management fee is 2-3% of the committed capital, the cost basis of investments, or a combination of both, depending on the fund stage and strategy.

Some funds may offer preferential management fee terms to anchor investors, who are the first or largest investors in the fund. To the extent there are any excess management fees left after paying the costs of running the firm (including salaries), this income can be divided among the team members.

In the context of a mature GP Entity team (i.e., a team that has successfully raised a number of funds), these excess spoils are typically allocated only among the senior partners. In the context of a first-time fund, once again, this pool is most often allocated evenly among all partners.

See Should you give an anchor investor a stake in your fund’s management company

1.4 Salary Allocations

This is the amount of money that the co-partners of the ManCo Entity receive as employees of the entity.

Typically, the salary allocations are based on the roles, responsibilities, and needs of the co-partners, and may be adjusted against their share of the carried interest pool (if any).

A fundamental concern is the trade-off between taking capital out as compensation, vs. leaving it in the management company to pay for more staff, technology, and other assets which increase the business’s value.

Often, salary paid today is considered a reduction in future payment of carry, if any, with some adjustment for the time value of money. The co-partners of the ManCo Entity need to agree on how to set and pay their salaries, provide raises in the future, and how to balance those ongoing obligations with the management fee income and the operational expenses. In addition, the salary allocations may be adjusted against a person’s share of the carried interest pool based on individual needs.

The salary allocations should also be fair and consistent with the market standards and the expectations of the investors. If certain team members have a need for a higher salary (for example, to support a family), it is often recommended to allocate more salary to that person as an advance against such person’s share of the carried interest pool.

This structure allows those team members who may need more income on an annual basis to receive it, while maximizing the equality and/or simplicity of the economic allocation of the fund’s profits among the team members.

For benchmarks, see VC compensation data and recruiters list.

That said, of course, the net present value of your income is greater if you’re getting your share of the economics earlier, and in addition you need to plan for the risk that the fund may not generate enough carry to pay for the advance that a given partner received.

Typical language to mitigate these risks is as follows:

“Each partner who receives an advance against his/her/their share of the carried interest pool shall be obligated to repay the advance if the fund does not generate sufficient carried interest to cover the advance. The repayment shall be made from any future distributions of carried interest or other compensation due to the partner. Advances against carried interest shall accrue interest at a rate of [X]% per annum. This interest will be added to the repayment obligation, ensuring that the fund is compensated for the time value of money.”

1.5 Changes in the Composition of the GP Entity and ManCo Entity Teams

This is to address the possibility that the co-partners of the GP Entity and the ManCo Entity may leave, join, or change their roles over time.

Typically, the changes in the composition of the teams are addressed on a case-by-case basis, with new partners usually not sharing in the economics of pre-existing investments.

The co-partners of the GP Entity and the ManCo Entity need to agree on how to handle these changes, and how to protect their interests and rights. The changes in the composition of the teams should also be communicated and approved by the investors, who usually want to see stability and continuity in the management of the fund.

1.6 Dividends Policy

We typically recommend that issuance of dividends from the management company, as opposed to reinvesting in the firm, requires two-thirds agreement of the owners of the management company.

1.7 Budget/operating expenses

The legal docs do not usually cover the particulars of operating expenses, but it’s important the leadership team is aligned on how this is budgeted.

2. Succession Planning Preparation and Policy

Succession planning is often a critical aspect of managing a venture capital firm, especially when one or more senior members of a VC firm are considering retirement within the next five to ten years. Proper succession planning ensures the continuity and stability of the firm, aligns the interests of the remaining partners, and maintains the confidence of investors.

Although this topic is too detailed and complex to cover in depth in this article, set forth below are examples of provisions that venture capital firms should consider including in the agreement that governs the rights and obligations of the various members.

2.1 Full-Time Commitment and Restrictions on Outside Activities

“Each partner shall devote his/her/their full business time and attention to his/her/their obligations to the firm. Specifically, each partner shall not spend more than 45 business days per year on vacation and/or on medical leave and shall not sit on more than one nonprofit board.”

2.2 Incapacity or Retirement Provisions

The agreement that governs the rights and obligations of the various members should include clear language regarding a situation where a partner is incapacitated or retires for any reason.

For example:

“Upon the incapacity or retirement of a Partner, the remaining Partners shall have the right to purchase the retiring Partner’s interest in the firm at a fair market value, as determined by an independent valuation firm.”

Or

“Any Partner that intends to retire from the firm must provide a minimum of 12 months’ notice prior to retirement to allow for a smooth transition and knowledge transfer to remaining Partners.”

2.3 Mandatory Retirement Age

Consider inserting a provision setting forth a mandatory retirement age to ensure a planned and orderly transition. For example:

“All Partners shall retire upon reaching the age of 65. Upon retirement, the Partner’s interest in the firm shall be reallocated among the remaining Partners based on their respective ownership percentages.”

2.4 Transition of Responsibilities

Clearly outline the process for transitioning responsibilities from the retiring partner to the remaining partners. For example:

“The retiring Partner shall mentor and train a designated successor for a period of 12 months prior to retirement. The successor shall be selected by unanimous consent of the remaining Partners.”

2.5 Communication with Investors

Ensure that changes in the composition of the team are communicated and approved by the investors. For example:

“Any changes in the composition of the Partners, including the retirement of a senior Partner, shall be promptly communicated to the investors. The approval of the Limited Partner Advisory Committee (LPAC) or a majority in interest of the limited partners shall be required for any such changes.”

See Alan Feld’s valuable essay on How to plan for GP succession. We also recommend:

3. Control/Operational Issues

The control/operational issues relate to how the decisions and actions of the fund, the GP Entity, and the ManCo Entity are made and executed by the co-partners. These include the following items.

3.1 Investment Decisions

These are the decisions that the GP Entity makes regarding the selection, valuation, and exit of portfolio companies.

Typically, the investment decisions are made by an investment committee with a unanimous consent mechanism, or a majority vote with a veto right for the managing GP/CEO or senior partners.

Many GP Entities will put in place a “unanimous consent” or “unanimous consensus” mechanism, allowing one member to essentially veto a particular investment if he or she has reservations or concerns about it. The co-partners of the GP Entity need to agree on how to form and operate the investment committee, and how to resolve any conflicts or disputes. The investment decisions should also be consistent with the fund’s strategy and objectives, and the investors’ expectations and preferences.

The modal disagreement inside a VC firm: partner X invested in a portfolio company, which is now performing below expectations. partner X wants to invest more money because she’s on the board, has a closer relationship with the CEO, and failure will reflect poorly on her personally. The other partners have lost faith and want to cut their losses. What should the firm do?

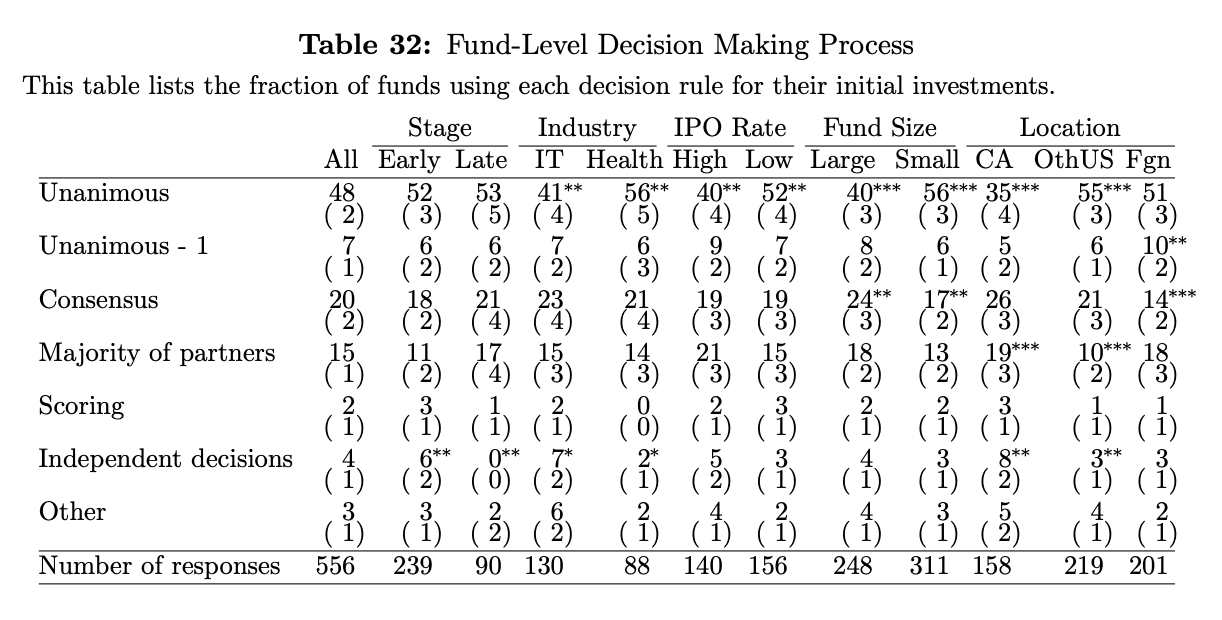

According to the research paper How Do Venture Capitalists Make Decisions?, “Roughly half the funds [surveyed] — particularly smaller funds, healthcare funds and non-California funds — require a unanimous vote of the partners. An additional 27% of funds require consensus (20%) or unanimous vote less one (7%). Finally, 15% of the funds require a majority vote.” For more on this, see An Inside Look at how Venture Capital Firms Make Decisions.

Bloomberg Beta open-sources their entire operating manual on GitHub, where their website lives. The whole document is worth reading, but most relevant is this excerpt:

“We have an “anyone can say yes” policy. Yes, any of our team members can say yes. And no, you don’t have to meet my other partners. We believe the best founders and companies are polarizing. Our best investments might have been, originally, opposed by one or more of our partners. Teams are great at gathering information and surfacing wisdom, but terrible at making decisions. We believe in individual accountability — if anyone can say yes, then everyone feels the weight of making a decision. (That said, we do require that before anyone says yes, they mention the investment to the rest of us — that way they get the benefit of the team’s input, and it’s a good way to slow down and think for a second.)”

An opposite extreme: TechCrunch asked Jeff Clavier, Founder of SoftTech VC, “With three full partners, what will the voting structure be at SoftTech? Will your vote carry more weight than your new partners or will two out of three votes get a deal done?”.

He said: “ Everyone has to support a deal in order to get it done. There is always a champion with strong conviction advocating for the deal, and he or she leads the due diligence. If and when there is a skeptic, we’ll often have that person participate in the due diligence phase to make sure all questions or doubts are answered. There is obviously respect amongst us as a team, and if one of us really wants to do a deal where he or she has an established track record, others will defer and support – unless the “over my dead body” card is pulled, in which case we pass. ”

3.2 Hiring/Firing of Team Members and Other Employees

These are the decisions that the GP Entity and the ManCo Entity make regarding the recruitment, retention, and termination of their personnel.

Typically, the hiring/firing of team members and other employees is controlled by senior members, with stringent standards for senior partners.

The co-partners of the GP Entity and the ManCo Entity need to agree on how to delegate and exercise this authority, and how to comply with the legal and ethical obligations. Note that designated key persons must devote substantially all their business time to the affairs of the fund and related activities, and failure to meet this requirement typically constitutes “cause” for removal under the applicable operating agreements. For example, committing an act of fraud against the underlying fund or the GP Entity — particularly acts that have a material adverse effect on the fund — will almost always constitute a “cause” event and give rise to a removal right.

Likewise, conviction of most felonies — particularly ones involving the misappropriation of assets — usually results in the right to remove the team member from the GP Entity. On the other hand, personal felonies — for example, a conviction for driving under the influence of alcohol or driving while impaired — may result in a “black eye” for the management team but may not necessarily result in the culprit being removed.

The hiring/firing of team members and other employees should also be aligned with the fund’s culture and values, and the investors’ trust and confidence. Partners will normally want to negotiate protection against constructive termination; an ability to resign without cause, covering notice period, obligations to the firm such as board service, etc.; and indemnification and D&O insurance.

3.3 Operational Decisions

These are the decisions that the GP Entity and the ManCo Entity make regarding the administration, governance, and compliance of the fund and the entities.

Typically, the operational decisions require varying levels of consent, often unanimous for material issues.

The co-partners of the GP Entity and the ManCo Entity need to agree on how to define and categorize the operational decisions, and how to implement and document them. The operational decisions should also be in accordance with the fund’s legal and tax structure, and the investors’ rights and obligations. In our experience, control over the most important operational decisions often is held by the most senior members of the firm. The more material the issue, the more likely that any such decision will require “unanimous consent” or “unanimous consensus.”

Examples of these operational issues include the following: admission of new partners to the GP Entity (including by way of transfer and by way of issuing new interests); negotiation of the fund terms with investors; when to call capital from fund investors and the members of the GP Entity; voting the securities of portfolio companies and other management decisions at the portfolio companies; selection of service providers and professional advisors; timing and amount of distributions from the fund to the LPs and from the GP Entity to its members; incurring indebtedness or entering into contracts (for the GP Entity or the underlying fund); liquidation-related decisions; valuation of underlying fund assets/GP assets; seeking an amendment to the underlying fund limited partnership agreement or the GP Entity limited liability company agreement; day-to-day and other decisions regarding the management of the GP Entity or the underlying fund.

4. Restrictive Covenants

The restrictive covenants are the agreements that the co-partners of the GP Entity and the ManCo Entity make to limit their activities and behavior that may harm the fund or the entities.

4.1 Level of Commitment and Restrictions on Outside Activities

These are the agreements that the co-partners of the GP Entity and the ManCo Entity make to dedicate their time and attention to the fund and related activities, and to refrain from engaging in competing or conflicting interests.

Typically, the level of commitment and restrictions on outside activities are high for key persons and senior partners, and lower for junior partners and advisors. For example, the designated key persons typically must devote substantially all of their business time to the affairs of the fund and related activities.

During the period of time when a team member is still a part of the enterprise, it is important to clearly lay out the ground rules as to how much “time and attention” needs to be spent on fund-related business. For example, will this be a full-time commitment of the team member, or something less? Even if it is a full-time commitment, what other activities outside the management of the underlying fund(s) may a team member pursue? The co-partners of the GP Entity and the ManCo Entity need to agree on how to specify and enforce these agreements, and how to accommodate any exceptions or waivers. The level of commitment and restrictions on outside activities should also be reasonable and proportional to the role and contribution of each co-partner, and the expectations and interests of the investors.

We recommend that if partners earn any time-based income outside of the Partnership, e.g., speakers’ honoraria, expert network consulting, board fees, etc., that compensation goes to the Partnership. This mitigates concern about partners spending time on personal income-producing activities. If a conference offers to pay a partner $10K, it seems a shame to leave the money on the table, but also, it’s unhealthy for a partner to be thinking about how to make extra money outside of his core job.

Additional resources:

4.2 Investment Opportunities

These are the agreements that the co-partners of the GP Entity and the ManCo Entity make to offer the fund the first right to invest in any opportunities that fall within the fund’s scope and strategy, and to avoid “cherry picking” or favoring other funds or entities.

Typically, the investment opportunities are subject to clear internal policies and procedures, and to disclosure and approval by the investment committee or the investors. The co-partners of the GP Entity and the ManCo Entity need to agree on how to identify and present the investment opportunities, and how to resolve any conflicts or disputes.

The investment opportunities should also be consistent with the fund’s fiduciary duty and best interest, and the investors’ consent and participation.

4.3 Dispute Resolution Mechanisms

These are the agreements that the co-partners of the GP Entity and the ManCo Entity make to settle any internal policy violations, disagreements, or controversies that may arise among them or with the fund or the investors.

Typically, the dispute resolution mechanisms include arbitration, mediation, or litigation, depending on the nature and severity of the issue.

If there is any ambiguity as to whether or not these internal policies have been violated, it is very important for the agreement governing the GP Entity to have some clearly defined dispute resolution mechanism — preferably arbitration, so that any such disputes can be resolved relatively quickly and in a confidential manner. The co-partners of the GP Entity and the ManCo Entity need to agree on how to choose and apply the dispute resolution mechanisms, and how to comply with the outcomes and remedies.

The dispute resolution mechanisms should also be fair and efficient and respect the rights and obligations of all parties involved.

4.4 Non-Compete and Non-Solicitation Covenants

These are the agreements that the co-partners of the GP Entity and the ManCo Entity make to refrain from competing with the fund or the entities, or soliciting their personnel, investors, or portfolio companies, during or after their association with the enterprise.

Typically, the non-compete and non-solicitation covenants vary by jurisdiction and should be crafted with legal counsel.

The co-partners of the GP Entity and the ManCo Entity need to agree on how to define and enforce these covenants, and how to accommodate any exceptions or waivers. The non-compete and non-solicitation covenants should also be reasonable and proportional to the role and contribution of each co-partner, and the expectations and interests of the investors. Do note, however, that non-compete clauses are generally unenforceable in California due to the state’s strong public policy favoring open competition and employee mobility.

While there are limited exceptions related to the sale of a business, dissolution of partnerships, and LLCs, the overarching principle remains that individuals should be free to pursue their professions without undue restrictions.

4.5 Carried Interest Vesting Schedules

As mentioned above, these are the agreements that the co-partners of the GP Entity make to condition their receipt of the carried interest on their continued association with the enterprise.

Typically, the carried interest vesting schedules are based on the investment period of the fund, with variations for more mature fund sponsors. The co-partners of the GP Entity need to agree on how to set and adjust the carried interest vesting schedules, and how to handle any departures or changes.

The carried interest vesting schedules should also be aligned with the fund’s performance and objectives, and the investors’ incentives and retention.

4.6 Attribution of the Fund’s Track Record

These are the agreements that the co-partners of the GP Entity make to share the credit and reputation of the fund’s investments and exits among themselves.

Typically, the attribution of the fund’s investments are done at the time of departure of one or more of the co-partners from a GP Entity.

That said, guidelines can be put in place at any time to help deal with this difficult (and often contentious) situation when it presents itself. It’s much healthier to document attribution at the time of investment, when everyone’s memory is fresh. One issue that can be settled up front that will also weigh on any decision of a team member to leave a GP Entity early involves attribution of the underlying fund’s track record. Here, the operative agreement of the GP Entity can make it clear that all investment results are deemed to have been achieved as a result of the combined efforts of all team members, as opposed to just one or two.

This pooling of attribution will make it much more difficult for a former team member to take the lion’s share of the credit with respect to successful investments (again, further incentivizing that team member to stay).

Conclusion

Forming a GP Entity and a ManCo Entity with co-partners for a fund is a complex and consequential process that requires careful consideration of the economic, control/operational, and restrictive covenant issues that will govern your relationship and your fund’s performance. By understanding the key terms and the best practices of other investors and their agreements, you can make smart decisions that will benefit you, your co-partners, your fund, and your investors.

About the author

David Teten is the founder of Versatile VC, which backs “investment tech” companies which help investors generate alpha. He is a Venture Partner with Orange Collective, a fund of 150+ Y Combinator alumni backing Y Combinator founders. David is Chair of AltsTech, a community of investors in private companies using AI, technology and analytics to generate alpha, and Founders’ Next Move, for tech founders exploring new ideas. He was formerly a Partner with Coolwater Capital, which invests in emerging fund managers as a limited partner, into general partnerships, and into fund management companies. He was also formerly a Managing Partner with HOF Capital; Partner with ff Venture Capital; and Founder of Harvard Business School Alumni Angels of NY. He started his career as a strategy consultant, Bear Stearns investment banker, and serial founder with 2 exits as CEO.

Dolph Hellman, a leading fund formation and commercial finance lawyer in the San Francisco office, is the Co-Chair of Orrick’s Private Investment Funds Group and a member of the firm's Corporate Department. Dolph concentrates his sophisticated practice on private equity investor representation and fund formation as well as representing financial institutions and corporations in privately negotiated debt transactions. In addition, Dolph has a broad range of experience in commercial lending transactions, including secured financings, unsecured and asset-based financings, vendor and customer financings, subscription credit facilities, project financing, venture debt financings, letters of credit, receivables purchase financings and leasing.