Among the various instruments available to startups for raising capital, the Simple Agreement for Future Equity (SAFE) has gained traction since its introduction by Y Combinator in Silicon Valley.

Although termed “simple,” a SAFE is a complex instrument with nuanced terms that both companies and investors need to understand thoroughly. While many people in the startup space are familiar with the SAFE basics, some terms might be less emphasized for two reasons: different SAFE forms have evolved over time, and the general terms of a SAFE form can be tailored to specific party needs, leading to a mix of standard and unique clauses. In general, the SAFE provides an inventive way for startups to raise initial funds without the complexities or constraints of debt.

This article aims to highlight lesser-discussed SAFE terms that might require negotiation.

Warning: this is not legal advice.

Table of Contents

A Brief Overview of SAFE for Beginners

Before exploring the detailed aspects of SAFE negotiation, it is essential to grasp its fundamental purpose.

So, what is a SAFE?

A SAFE is an innovative financial tool used by startups to raise capital. It allows investors to provide funds to a company in exchange for the right to obtain equity at a future date, under specific conditions. For investors, it is a bet on the company’s potential success, with the understanding that their investment will convert into equity, typically during a significant funding event.

Unlike convertible notes, SAFEs are not loans. They do not accrue interest nor have a maturity date (this also means that if a startup fails, SAFE holders do not have the same claim to assets that debt holders might). Further, while the SAFE is a convertible instrument that might convert into preferred stock, at the time of the SAFE round, a corporation’s certificate of incorporation does not have to be amended to authorize the issuance and set forth the rights of such preferred stock. So, occasionally, entrepreneurs argue that SAFE financings involve minimal negotiation because the primary discussions only revolve around two big items: the investment amount and the valuation cap.

Why should I use a SAFE to raise for my company anyway?

First of all, it is worth mentioning that SAFEs are not suitable for all deals or companies. Particularly, companies not expecting significant funding rounds in the future might find that SAFEs do not align with their long-term capital raising strategy. This is because SAFEs are inherently designed to convert into equity during such funding events. Moreover, certain investors may prefer more traditional securities instruments that offer more defined terms and timelines.

That being said, SAFEs can be advantageous as they enable a company to raise funds without pinning down a valuation and by extension, a price per share. The formula universally recognized is: Price per Share = Valuation / Fully-Diluted Capitalization. Determining a valuation can be a difficult and time-consuming process, especially for companies that are pre-revenue and other early-stage companies.

A SAFE lets both parties defer the moment of the valuation determination until a later date, which is expected to be when the company and a future lead investor agree on a valuation and resulting share price for preferred stock. Valuation disputes can be a common source of tension between early-stage companies and their investors and using a SAFE instrument can help to avoid such disputes and maintain a positive relationship between the company and its investors.

Find ideal VCs for your startup today 🚀

Share pitch decks, track engagement, and get replies from investors - all within your FREE Fundraising CRM.

Pre-money vs post-money SAFEs

Pre-money and post-money SAFEs are two structures that define how ownership and valuation work in a startup’s capital-raising process when using a SAFE (Simple Agreement for Future Equity). They differ primarily in how they calculate an investor’s ownership percentage once the SAFE converts to equity, usually at a later funding round.

1. Pre-money SAFE

In a pre-money SAFE, the investor’s ownership is calculated based on the company’s valuation before the SAFE investment is considered. This structure does not include the SAFE investment in the company’s valuation, which can create more dilution for founders and existing shareholders because future rounds don’t account for the SAFE funds in the valuation.

For example, if a company is valued at $10 million (pre-money) and an investor puts in $1 million using a pre-money SAFE, the investor’s ownership percentage will be calculated based on the original $10 million valuation. However, when the SAFE converts, the dilution caused by the SAFE itself can sometimes surprise founders, especially when multiple SAFEs are outstanding.

2. Post-money SAFE

A post-money SAFE, on the other hand, calculates the investor’s ownership based on the company’s valuation after the SAFE investment. This approach provides more clarity to both founders and investors about dilution and future ownership because it considers the SAFE investment as part of the company’s total valuation.

Using the same example, with a post-money SAFE, the $1 million investment would be factored into the company’s new post-money valuation of $11 million, giving the investor a clearer and fixed percentage of ownership relative to the total valuation (including all SAFE investments). This structure allows founders to better predict their dilution and is now the more commonly used form, especially after Y Combinator introduced post-money SAFEs to help founders manage ownership expectations.

When the SAFE Conversion is Optional

A milestone for post-SAFE financing companies is the closing of the first priced equity round. Typically, a SAFE instrument will contain language that will provide for the immediate conversion of the SAFE upon the occurrence of a priced equity round.

However, sometimes the SAFE language grants companies discretion on timing for conversion. Companies then have the choice to convert the SAFEs or to leave them outstanding. What are the risks for investors if a SAFE lacks mandatory conversion stipulations? Suppose a company successfully achieves initial funding through a SAFE issuance during the course of a Pre-Seed, Seed Round, or bridge round (however you might want to call it) and later issues preferred stock in a Series A round, becomes highly profitable, and distributes dividends. SAFE holders won’t receive dividends or other distributions. Their SAFE investment remains outstanding with no voting power, potentially tying up the investor’s capital for a long time. This can be an issue as, for an investor, the idea behind a SAFE investment is to eventually convert the initial investment into company equity.

What Kind of Financing Events Trigger SAFE Conversion?

Not all financing rounds may trigger a SAFE’s conversion, and conditions may vary. Typically, SAFEs employ the term of “equity financing” to refer to qualifying priced rounds, with varying definitions. A majority of SAFEs define equity financing as the issuance of preferred stock for capital raising purposes at a fixed valuation. Other instruments require a minimum fundraising threshold for conversion (often $1-2M for early-stage companies).Investors often prefer a restrictive definition for the qualifying financing event, especially when the conversion means receiving the same stock as new investors.

If a company attracts modest seed funding, the rights attached to the stock being sold might not entirely satisfy SAFE investors. Rather, they anticipate a subsequent substantial investment with a preferably robust lead investor, hoping to obtain better rights than seed investors (e.g. seniority, liquidation multiple, director seats, or protective provisions which may allow them to veto certain company decisions). Hence, understanding the exact equity financing event triggering a SAFE conversion is crucial.

Crowdfunding tip

Avoid solely using “Preferred Stock” language to define that financing event, as many companies may later choose to issue common stock in a Reg A offering, which could be a suitable conversion event for both the company and the investors.

The Fine Print: Why Fully Diluted Capitalization Matters

In the event of a qualifying financing, most SAFEs convert based on 1) the conversion cap formula, 2) the discount formula, or 3) the formula yielding the most shares - the last being the most investor-friendly.

Understanding the Discount Formula

Calculating the conversion price using the discount formula is relatively straightforward: If the SAFE converts into equity in connection with an equity financing round, the SAFE holder gets shares at a price discounted from what new investors pay, typically by 20%. Easy enough.

The Valuation Cap Formula

A bit more complicated, and thus the focus of this discussion, is the valuation cap formula. A valuation cap determines the maximum company valuation at which the SAFE amount will convert into equity. If the company’s next equity financing round values the company at a higher valuation than the cap, the investment amount of SAFE holders will convert into equity at the capped valuation, ensuring them a more favorable price per share (i.e., the conversion price) than the price paid by the investors who initiated the Equity Financing. However, even if the valuation cap is defined in the SAFE instrument, the corresponding conversion price is not set in stone. That is where you want to carefully look at the definition of fully diluted capitalization and what it precisely comprises.

The Importance of Fully Diluted Capitalization

The fully diluted capitalization refers to the total number of outstanding shares of stock of a company, taking into consideration the potential conversions of outstanding convertible instruments. The fully diluted capitalization essentially represents the total number of shares that would exist if all convertible rights were exercised. Why does this matter? Because under the valuation cap formula, the conversion price will be determined by dividing the valuation cap amount by the fully diluted capitalization of the company, as defined in the SAFE instrument. If the fully diluted capitalization is a high number, the resulting conversion price will be low; and, thus, the more shares the investor will receive for a given investment amount.

Components Affecting Ownership for SAFE Holders

The components included in the fully diluted capitalization definition directly affect how much ownership SAFE holders receive when the SAFEs convert. There are several items that can be included or excluded from a company’s fully diluted capitalization. The fully diluted capitalization of the company, depending on what it and its SAFE investors agree upon, typically includes all issued shares of common stock, as well as shares of preferred stock calculated on a converted basis, as well as issued options and warrants. However, in order to keep the conversion price low, investors will typically want to include shares that have not necessarily been issued but instead have been reserved for the employee stock option plan (the “option pool”).

Further, they might negotiate that the definition includes any increase in the shares reserved for the employee stock option plan. More commonly, investors might push to include convertible instruments such as Convertible Notes and SAFEs as well. You get it - by neglecting to carefully define or examine what is included under the fully-diluted capitalization definition, company founders might give SAFE holders more equity than the founders expected.

Amending the Terms of Outstanding SAFEs

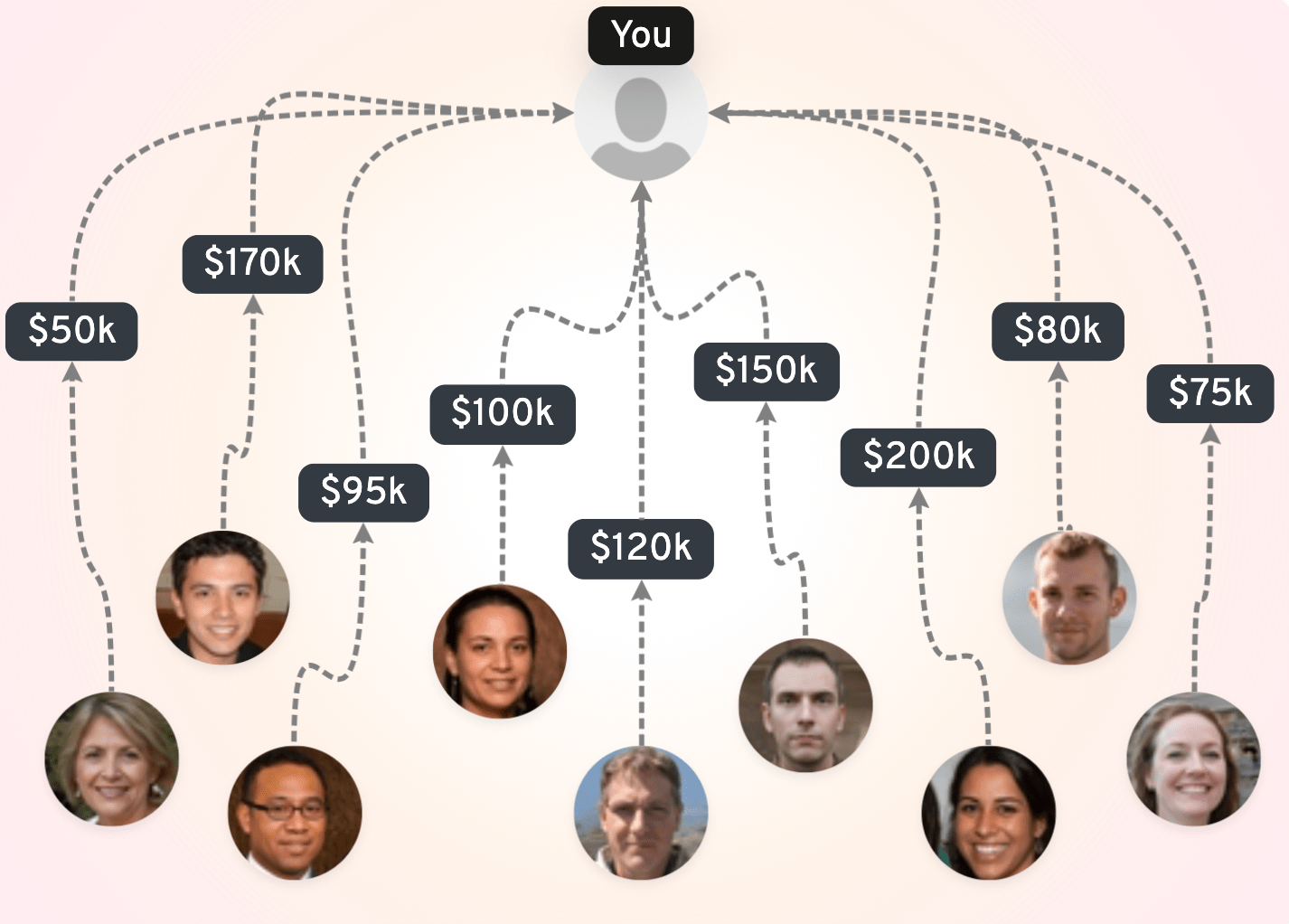

Now, a few words to founders who want to issue SAFEs to more than one investor. Sometimes, amendments to outstanding SAFES are required, whether for compliance purposes, to ensure consistency or meet the requirements of new investors, or just because the company has to undergo structural changes (think about the transition of an LLC to C-corp).

When multiple investors have signed a SAFE, coordinating amendments can become a logistical challenge, especially if some SAFE investors are reluctant. In order to achieve a seamless amendment process, founders should make sure that the SAFE instrument contains flexible amendment provisions. In particular, founders may propose language that permits the amendment of an entire SAFE round with the vote of the majority-in-interest of all holders of that SAFE round, meaning, the vote of the SAFE investors whose combined SAFEs total more than 50% of the aggregate SAFE round.

In the presence of numerous investors, founders won’t have to get amendment approval from each single individual investor. Instead, they can simply address the majority and streamline the amendment process. If the majority-in-interest of all holders of SAFE agree to the amendment, all identical SAFE instruments will be amended in the same way, in spite of the potential refusal of minority SAFE holders. However, most amendment provisions contain certain safeguards prohibiting the amendment of the initial investment amount. The SAFE amount paid by investors is typically sacrosanct and cannot be changed.

The problem with stand-alone SAFEs

The last item this article will address is the emphasis on the SAFE instrument being typically a very short document, which can allow companies to get funded in a fairly short amount of time. The brevity of the legal work around the SAFE is undoubtedly one of its biggest selling points. But the devil is in the details.

Keep in mind that any business still needs very specific representations in any investment contracts in order to be adequately protected. While stand-alone SAFEs have become popular in rounds that are only open to accredited investors pursuant to Rule 506(c), in the absence of explicit representations, a company may inadvertently assume unforeseen liabilities or risks.

If no complete Private Placement Memorandum is made available to SAFE investors in connection with the investment opportunity, the classic SAFE form will often lack comprehensive and tailored representations - a series of statements confirming the current status and health of the company and addressing any applicable issues. Needless to say, it might be hard to ensure transparency between the company and its investors when the only governing document is condensed in often no more than 5 pages. And yet, it is not advisable for a company to sell a stand-alone SAFE that fails to protect the issuer against investor claims.

Another common mistake for startups is to focus solely on the simplicity and speed of the SAFE signature process, overlooking applicable and important securities laws. SAFEs are still securities instruments and issuing them triggers a range of legal obligations under federal and state securities laws. Ensuring compliance often necessitates the inclusion of specific language in the SAFE instrument to address the company’s adherence to securities laws, including representations about the company’s status, disclosure of material information, and confirmation of the investors’ accreditation status. This is why a company and its legal team should ensure that all potential compliance or disclosures issues have been identified and then include in the SAFE instrument all needed representations tailored to the company’s unique situation. Being cost-effective and moving rapidly in the world of SAFEs without proper due diligence and disclosure can be a risky game that companies might regret playing.

Conclusion

Understandably, there is more to a SAFE form than negotiating the valuation cap and the ticket size. This article touches upon only a handful of potential discussion points, but there are of course other terms, and SAFE instruments come in diverse forms. For founders, a deep understanding of these nuances ensures informed decision-making and sets clear expectations about the investment structure. Always remember, while SAFEs offer simplicity in their design, understanding their implications requires careful attention to detail, and often, some sophisticated negotiation.

Find your ideal investors now 🚀

Browse 5,000+ investors, share your pitch deck, and manage replies - all for free.

Get Started

About the author

- Attorney Advertising -

Côme Laffay, Esq. is a corporate and securities attorney. He is Counsel at KBL Roche, a transatlantic full-service boutique law firm with offices in New York, Paris, and Munich. Côme's practice focuses on capital raising activities in both the private placement and the crowdfunding spaces, with the goal of supporting entrepreneurs and financial intermediaries.

KBL Roche

1115 Broadway, STE 1011 New York, NY 10010

[email protected]

(646) 801-6171